The Badge and the Myth

Photography has always been more than a technical act. From its very beginnings, it has been a way of performing identity, of declaring values, and of negotiating the balance between convenience and control. Few phrases capture this tension better than the oft-repeated boast: “I did it all in camera.”

On the surface, the phrase sounds simple enough. It is a claim of purity, a suggestion that the photograph is untainted by manipulation, that the photographer’s skill lies in capturing the world exactly as it was. To say it is to imply that the image is somehow more authentic, more trustworthy, or more virtuous than one that has been altered after the shutter was pressed. It is a badge of honour, worn proudly in conversation, in captions, and in the lore of photographic culture.

But the history of photography complicates this claim almost immediately. From the earliest daguerreotypes to today’s AI-assisted workflows, every photograph has been shaped by choices made both inside and outside the camera. Exposure times, lens selection, chemical recipes, paper stocks, digital sensors, software defaults — all of these are interventions. Even the decision of where to stand and when to press the shutter is a form of manipulation. The idea that a photograph can ever be entirely “pure” is, at best, a comforting illusion.

And yet, the illusion matters. The badge of honour is not really about truth; it is about identity. It is about how photographers want to be seen by their peers, their audiences, and themselves. To claim that you “did it all in camera” is to position yourself within a particular tradition, to align yourself with a set of values: discipline, restraint, mastery of craft. It is a way of saying, “I rely on skill, not on trickery.” Whether or not that claim holds up under scrutiny is almost beside the point. What matters is the performance of integrity.

This badge has shifted in meaning over time. In the nineteenth century, when photography was inseparable from chemistry, the idea of doing it all in camera would have been nonsensical. In the Kodak era, when amateurs could simply press a button and send their film away, it became a mark of distinction for those who insisted on developing and printing their own work. In the twentieth century, the darkroom became a stage for artistry, and the badge was claimed both by purists who prized the decisive moment and by printers who transformed negatives into performances of light and shadow. In the digital age, the badge became a defensive gesture, a way of resisting the perceived excesses of Photoshop. And today, in the age of AI, it is both a rallying cry and a relic, invoked by those who resist automation and dismissed by those who embrace it.

What makes the phrase so enduring is not its accuracy but its symbolism. It speaks to a deep human desire for authenticity, for a sense that what we are seeing is “real”. It also speaks to the competitive nature of photographic culture, where claims of skill and purity are used to establish hierarchies of value. To say you did it all in camera is to draw a line between yourself and others; between the disciplined and the careless, the authentic and the artificial, the artist and the technician.

This essay traces the history of that badge from the birth of photography, through Kodak’s democratisation of the medium, the prestige of the darkroom, the digital revolution, and finally the age of AI. Along the way, we will ask: what does it really mean to “do it all in camera”? Why has this phrase carried such weight for nearly two centuries? And perhaps most importantly, what does it reveal about the way photographers see themselves, and the way they want to be seen?

The Birth of Photography: Chemistry, Craft, and Control

When Louis Daguerre announced his photographic process in 1839, the world marvelled at its ability to fix an image of reality onto a silvered plate. Newspapers of the time described it as almost magical: a way of capturing nature’s own drawing without the intervention of the human hand. Yet the process was anything but simple. Exposures could take several minutes, requiring sitters to remain rigidly still, often supported by hidden clamps or braces to prevent the slightest movement. The plates themselves had to be sensitised with iodine vapour, developed with mercury fumes, and fixed with salt or hypo. The entire procedure was laborious, hazardous, and highly technical.

In this context, the idea of “doing it all in camera” would have been meaningless. The camera was only one part of a complex chain of chemical and mechanical steps. The skill of the photographer lay as much in chemistry as in composition. To be a photographer in the 1840s was to be a chemist, a technician, and an artist all at once. The camera obscura might capture the light, but it was the darkroom that revealed the image, and the chemical bath that preserved it.

The daguerreotype, for all its brilliance, was a one-off object. Each plate was unique, fragile, and difficult to reproduce. William Henry Fox Talbot’s calotype process, announced in 1841, offered a different path. By producing a paper negative that could be contact-printed, Talbot introduced the principle of reproducibility into photography. But here, too, the artistry was inseparable from the darkroom. The texture of the paper, the quality of the chemicals, the precision of the exposure — all of these shaped the final image.

What is striking about this early period is how far it was from the later myth of the “straight” photograph. Every image was the product of intervention. Exposure times had to be judged by eye, often with little more than experience to guide the photographer. Development was a delicate balancing act, with seconds making the difference between a usable plate and a ruined one. Fixing and washing were equally critical, as any residue could cause the image to fade or discolour. Even the choice of support — polished silver, salted paper, or later glass — carried aesthetic and practical consequences.

The badge of honour at this stage lay not in avoiding manipulation, but in mastering the entire process. To be respected as a photographer was to demonstrate competence across a wide range of skills: preparing plates, mixing chemicals, handling dangerous substances, and coaxing an image into being. The notion of purity, of capturing reality “as it was” would have seemed absurd to practitioners who knew just how much labour and intervention went into every picture.

It is also worth noting that early photography was never entirely free from artistic manipulation. Daguerre himself was a painter and theatre designer, and his images often bore the marks of staging and composition. Talbot, too, was interested in photography as a tool for artistic expression, arranging still lifes and architectural studies with a painter’s eye. The idea that photography was a purely mechanical process, untouched by human intention, was more a rhetorical claim than a lived reality.

In short, the earliest photographers were not simply pointing a device at the world and recording what was there. They were engaged in a complex act of translation, turning light into chemistry, chemistry into image, and image into meaning. The badge of honour was not about restraint but about mastery. To “do it all” meant to understand and control every stage of the process, from the preparation of the plate to the final presentation of the print.

Key point: At this stage, there was no such thing as a “straight” photograph. Every image was the product of intervention — exposure, development, fixing, and printing. The badge of honour lay not in avoiding manipulation, but in demonstrating command over the entire chain of operations.

Sources:

National Gallery of Art, “Daguerreotype”.

Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography (Museum of Modern Art, 1982).

Kodak and the Democratisation of Photography

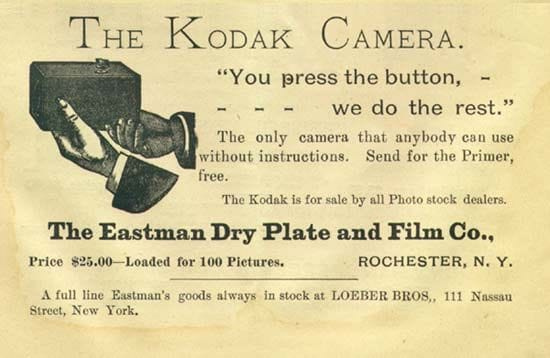

The real rupture in the story of photographic practice came in 1888, when George Eastman introduced the Kodak No. 1 camera. Its slogan was as bold as it was revolutionary: “You press the button, we do the rest.” With those words, Eastman reframed photography from a specialised craft into a consumer service. The camera itself was a simple box with a fixed-focus lens and a roll of film preloaded inside. Once the roll was finished, the entire camera was sent back to Kodak, where the film was developed, prints were made, and the camera was reloaded before being returned to the customer.

For the first time, ordinary people could take photographs without needing to master chemistry, optics, or the intricacies of darkroom practice. They no longer had to handle dangerous chemicals, mix solutions, or spend hours in dimly lit rooms coaxing an image out of a negative. Instead, they could simply point, click, and wait for the results to arrive in the post. Photography was no longer the preserve of the skilled practitioner; it was a pastime for the masses.

This shift cannot be overstated. Before Kodak, photography was a demanding pursuit, requiring not only expensive equipment but also a working knowledge of chemistry and a tolerance for mess and hazard. After Kodak, it became a leisure activity, something families could enjoy on holidays, at picnics, or in their own gardens. The photograph moved from the studio and the laboratory into the everyday lives of millions.

Yet this democratisation created a new divide. For professionals and serious amateurs, control over the process became a marker of distinction. To “do it all yourself” was to prove that you were not just pressing a button — you were shaping the image at every stage, from exposure to development to printing. The badge of honour began to take shape here: to say you developed your own negatives and made your own prints was to distinguish yourself from the masses who relied on Kodak’s labs.

For the casual snapshooter, however, outsourcing was not a weakness but a virtue. It meant convenience, consistency, and freedom from the mess of chemicals. It allowed them to focus on the moment rather than the mechanics. The family album, filled with Kodak prints, became a new cultural artefact, a record of ordinary lives that would have been unthinkable in the era of daguerreotypes and collodion plates.

The debate that emerged was not simply about technique but about values.

- Pro-lab: Convenience, accessibility, and the ability to focus on the subject rather than the process. Outsourcing meant that anyone could participate in photography, regardless of technical skill. It democratised memory itself, allowing families to preserve their lives in pictures without needing to become chemists.

- Pro-self: Control, artistry, and the satisfaction of mastering the medium. To develop and print your own work was to claim authorship in a deeper sense, to insist that the photograph was not just a record but a crafted object.

This tension between convenience and control would echo throughout the history of photography. Each new technological advance — from roll film to colour slides, from instant cameras to digital sensors — would reopen the debate. Was photography about ease and accessibility, or about mastery and craft? Was the badge of honour earned by pressing the button, or by doing the rest yourself?

In many ways, Kodak’s slogan set the terms of the debate that continues to this day. By separating the act of capture from the act of processing, it forced photographers to decide where they stood. Were they content to let others handle the messy, technical side of things, or did they insist on taking responsibility for the entire chain? The answer to that question became a way of signalling identity, of declaring whether one was a casual participant or a serious practitioner.

Sources:

Eastman Museum, “From the Camera Obscura to the Revolutionary Kodak”.

Twentieth-Century Film Culture — Negatives, Slides, and the Darkroom

The twentieth century was the period in which photography truly came of age. It matured into both an art form and a mass medium, shaping everything from family albums to advertising, journalism to fine art. Black-and-white negatives, colour slides, and roll film expanded the possibilities of capture, while new cameras made photography more portable, more flexible, and more responsive to the world. Yet with this expansion came a sharpening of the divide between what was achieved “in camera” and what was achieved afterwards, in the darkroom.

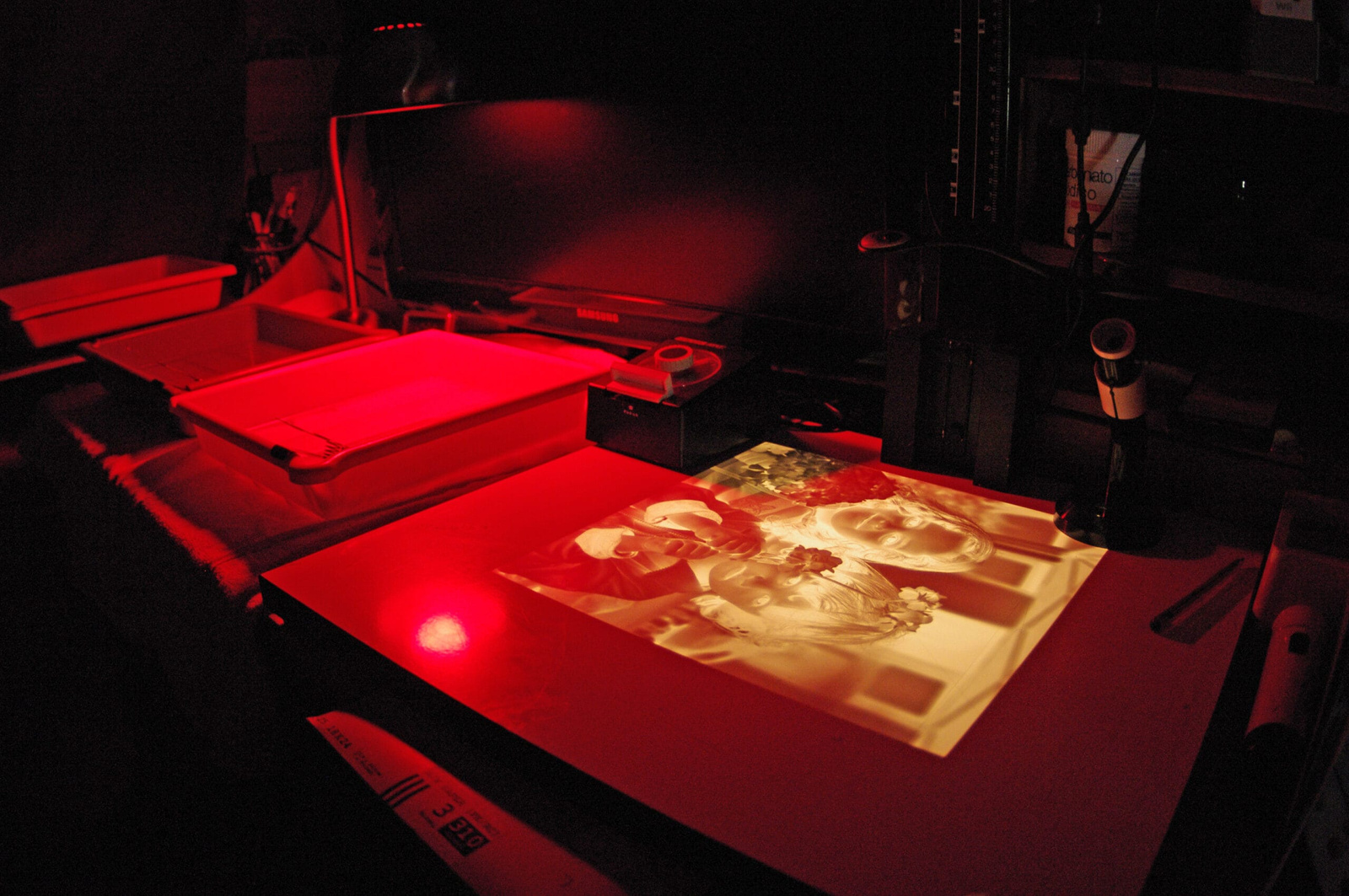

For many photographers, the darkroom was the true stage of artistry. It was here, under the glow of a red safelight, that the latent image on a negative was coaxed into being. Techniques such as dodging and burning allowed photographers to control local exposure on the print, brightening or darkening specific areas to guide the viewer’s eye. Contrast could be manipulated through paper choice, filters, or chemical adjustments. Toning processes — sepia, selenium, gold — could alter not only the colour but also the permanence of the print. The darkroom was not simply a place of reproduction; it was a place of interpretation.

Ansel Adams, perhaps the most famous advocate of darkroom mastery, captured this philosophy in his oft-quoted remark: “The negative is the score, the print is the performance.” For Adams, the act of pressing the shutter was only the beginning. The real artistry lay in the translation of that negative into a finished print, a process that could take hours of careful experimentation. His Zone System, developed with Fred Archer in the 1930s, was a method of pre-visualising the final print at the moment of exposure, but it was also a system that acknowledged the centrality of darkroom work. To expose correctly was to give oneself the raw material for later interpretation.

At the same time, another philosophy was taking shape. Henri Cartier-Bresson, working with a small Leica rangefinder, popularised the idea of the “decisive moment.” For him, the true artistry of photography lay in timing and composition at the instant of exposure. The darkroom, in his view, was a place of minimal intervention. His prints were generally straightforward, with little manipulation beyond basic exposure and contrast adjustments. What mattered was the alignment of form and content in a fleeting moment — the geometry of a scene, the gesture of a figure, the play of light and shadow.

These two positions — Adams’ darkroom mastery and Cartier-Bresson’s in-camera purity — came to symbolise a broader debate within twentieth-century photography.

- Doing it all in camera: This camp emphasised mastery of exposure, framing, film choice, and filters. The badge of honour here was the ability to anticipate and capture the image exactly as it should be, without relying on later correction. The decisive moment was not just about timing but about discipline, about seeing the world clearly and responding with precision.

- Darkroom mastery: This camp saw the negative as raw material, a starting point rather than an end. The badge of honour lay in the ability to transform that material into a work of art through careful printing. The darkroom was not a place of correction but of creation, where the photographer’s vision was fully realised.

But the debate did not stop there. The mid-century also saw the rise of colour photography, which introduced new complexities. Kodachrome slides, introduced in the 1930s, became the medium of choice for amateurs and professionals alike. They offered vivid colours and remarkable stability, but they were also notoriously difficult to process at home. Most photographers had to send their film to Kodak’s labs, effectively outsourcing the development stage. For purists, this raised uncomfortable questions: could one still claim authorship if the most critical part of the process was handled by a technician? For others, the brilliance of Kodachrome justified the compromise.

Colour also shifted the cultural perception of photography. Black-and-white had long been associated with seriousness, with art and reportage. Colour, by contrast, was often dismissed as commercial or frivolous. To work in colour was, in some circles, to risk being seen as less authentic. Yet by the 1970s, photographers like William Eggleston and Stephen Shore had begun to reclaim colour as a legitimate artistic medium, challenging the hierarchy that placed monochrome above all else. Here again, the badge of honour was contested: was it more authentic to stick with black-and-white, or more courageous to embrace colour despite its associations?

Meanwhile, the world of photojournalism raised its own ethical questions. The darkroom was not only a place of artistry but also of potential manipulation. Cropping, retouching, and selective printing could alter the meaning of an image, sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically. Controversies such as the debate over Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier (1936) — was it staged, or genuine? — highlighted the uneasy relationship between photography and truth. For photojournalists, the badge of honour lay in restraint, in proving that their images were faithful records of events. Yet even here, the line was blurry: was adjusting contrast to make a scene clearer an act of honesty, or of distortion?

The amateur/professional divide also widened during this period. For the amateur, photography was often about family, leisure, and memory. Holiday slideshows and family albums became cultural rituals, with Kodak prints and colour transparencies serving as tokens of everyday life. For the professional, by contrast, photography was about authorship, reputation, and artistic vision. The badge of honour was not in simply recording but in elevating, in proving that one’s work belonged in galleries and magazines rather than shoeboxes and living rooms.

What is striking is that both positions — the purist and the manipulator, the amateur and the professional — were, in their own way, performances of identity. To align oneself with Cartier-Bresson was to claim the mantle of the intuitive, the spontaneous, the artist who could see the world in a flash of recognition. To align oneself with Adams was to claim the mantle of the craftsman, the patient interpreter who could shape light and shadow into symphonies of tone. To embrace colour was to risk being seen as commercial, but also to claim boldness. To stick with black-and-white was to claim seriousness, but also to risk conservatism. Each position carried cultural weight, and each offered photographers a way of distinguishing themselves within a rapidly expanding medium.

The twentieth century, then, was not just a period of technical innovation but of philosophical debate. The camera and the darkroom became symbols of competing values: immediacy versus deliberation, purity versus interpretation, capture versus creation. And in all of these debates, the badge of honour was not simply about technique but about identity — about how photographers wanted to be seen, and how they wanted their work to be understood.

Sources:

Ansel Adams, The Print (New York Graphic Society, 1983).

John Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs (MoMA, 1973).

The Digital Revolution — SOOC vs. Post-Processing

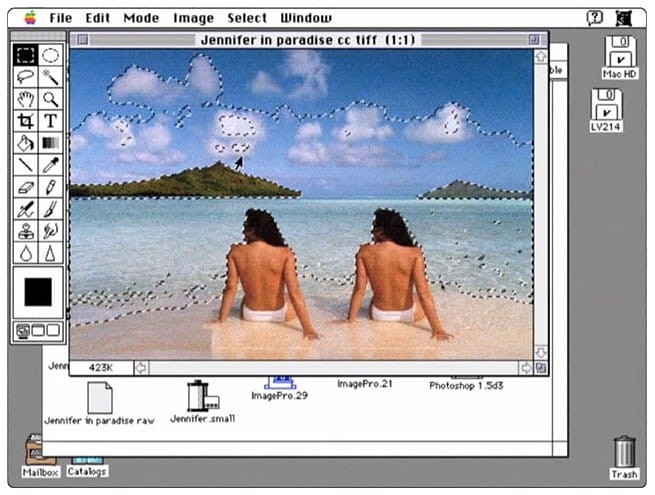

The arrival of digital photography in the 1990s and 2000s reignited the old debate about capture versus processing, but in entirely new terms. For the first time, photographers could manipulate images with unprecedented ease and precision. Adobe Photoshop, first released in 1990, quickly became the industry standard for digital editing, offering tools that could retouch, composite, and transform photographs in ways that would have been unthinkable in the darkroom. By the mid-2000s, Adobe Lightroom (2007) added a workflow-oriented approach, allowing photographers to manage, edit, and export large numbers of images with remarkable efficiency.

This technological leap changed not only how photographs were made but also how they were judged. Suddenly, “in camera” became a defensive position. To say that an image was “straight out of camera” (SOOC) was to claim authenticity in a world where digital trickery seemed to lurk around every corner. Online forums, photography clubs, and later social media platforms filled with debates between SOOC purists and post-processing enthusiasts. The phrase “no Photoshop” became a kind of disclaimer, a way of reassuring viewers that what they were seeing was “real.”

The RAW versus JPEG debate mirrored the old divide between self-developing and lab processing. Shooting JPEG meant letting the camera’s internal algorithms decide on colour balance, contrast, sharpening, and compression. It was quick, convenient, and often good enough for casual use. Shooting RAW, by contrast, meant capturing all the data from the sensor and taking control of the development process in software. It was the digital equivalent of developing your own negatives: more work, but also more control.

This divide was not merely technical; it was philosophical.

- SOOC purists argued for authenticity, honesty, and the skill of getting it right at the moment of capture. For them, the badge of honour lay in discipline: in mastering exposure, white balance, and composition so thoroughly that no further intervention was needed. They saw post-processing as a crutch, or worse, as a form of deception. The pride of the SOOC photographer was in restraint, in proving that the image was strong enough to stand on its own.

- Post-processors, on the other hand, championed creativity, flexibility, and the argument that editing was simply the new darkroom. They pointed out that every photograph, even a JPEG, was processed — the only question was whether the processing was done by the camera’s software or by the photographer. For them, the badge of honour lay in mastery of tools like Photoshop and Lightroom, in the ability to refine, enhance, or even radically transform an image to match their vision.

The badge of honour, then, shifted once again. For some, it lay in resisting the lure of Photoshop, in proving that their skill at the moment of capture was sufficient. For others, it lay in mastering Photoshop itself, in demonstrating that artistry did not end when the shutter closed but continued on the screen.

What made this debate particularly intense was the speed and visibility of digital culture. In the film era, darkroom manipulations were largely invisible to the public; only other photographers knew how much work went into a print. In the digital era, editing became both more obvious and more suspect. The rise of photojournalism scandals — where images were disqualified for excessive manipulation — reinforced the idea that post-processing was somehow dishonest. At the same time, the explosion of creative digital art, from surreal composites to hyper-real landscapes, showed that editing could be a legitimate form of expression in its own right.

The digital revolution, then, did not resolve the old tension between capture and process. It simply reframed it. The question was no longer whether to send your film to a lab or develop it yourself, but whether to trust the camera’s algorithms or to take control in software. And once again, the choice became a way of signalling identity. To declare yourself a SOOC purist was to align with authenticity and restraint. To embrace post-processing was to align with creativity and interpretation. Both sides claimed honour, and both sides saw themselves as defending the true spirit of photography.

Sources:

Martin Evening, Adobe Photoshop for Photographers (Focal Press, 2018).

Adobe, “Celebrating 35 years of creativity, community, and innovation with Adobe Photoshop”.

The Age of AI — The Badge in Question

Today, the rise of artificial intelligence has blurred the line between capture and process almost beyond recognition. What once required hours of careful darkroom work, or later painstaking digital editing, can now be achieved in seconds with a single click. Tools such as Adobe Firefly, DxO DeepPRIME, and Luminar Neo offer photographers the ability to denoise, sharpen, replace skies, or even generate entirely new elements with astonishing ease. The software does not merely enhance; it interprets, predicts, and invents.

For some, this is simply the next step in a long continuum. Just as Ansel Adams used dodging and burning to refine his prints, today’s photographers use AI to refine their images. From this perspective, AI is not a rupture but an evolution — another tool in the ever-expanding kit of photographic practice. The argument goes that every generation of photographers has embraced new technologies, from roll film to colour emulsions, from enlargers to Photoshop. Why should AI be treated any differently?

For others, however, AI represents a fundamental break. It is not merely a matter of enhancing what was captured but of creating what was never there. When a sky is replaced wholesale, or when a distracting element is erased and filled with invented detail, the photograph ceases to be a record of reality and becomes something closer to digital illustration. For these critics, AI undermines the very essence of photography as a medium rooted in the indexical trace of light.

The debate is fierce, and it often comes down to values rather than technique.

- Pro-AI: Advocates argue that AI represents democratisation, efficiency, and creative expansion. It allows photographers of all levels to achieve results that once required years of training. It saves time, reduces technical barriers, and opens up new avenues of expression. In this view, AI is no different from the introduction of autofocus or auto-exposure — technologies that were once derided as “cheating” but are now taken for granted. The badge of honour, they argue, lies not in resisting new tools but in using them with intention and imagination.

- Anti-AI: Critics counter that AI erodes skill, authenticity, and authorship. If the software is making decisions about what the image should look like, then who is the author — the photographer or the algorithm? They worry that the craft of photography, built on generations of accumulated knowledge about exposure, composition, and printing, will be lost. For them, the badge of honour lies in resisting the tide of automation, in proving that one can still “do it all in camera” without relying on machine intervention.

The badge of honour is now contested more fiercely than ever. To claim “I did it all in camera” is to resist not just post-processing but the very logic of automation. It is to align oneself with authenticity, discipline, and tradition. To embrace AI, by contrast, is to argue that the badge itself is outdated — that the true honour lies in adapting to the tools of the age, in recognising that photography has always been a hybrid of capture and process.

What makes the AI debate particularly charged is its visibility. Unlike subtle darkroom manipulations or even careful Photoshop edits, AI interventions can be dramatic and obvious. A sky that never existed, a person who was never there, a background that has been entirely fabricated — these are not refinements but inventions. The question then becomes: at what point does a photograph stop being a photograph? And does that distinction even matter in a world where images circulate more as symbols and impressions than as documents of reality?

The age of AI forces us to confront the badge of honour in its starkest form. Is photography about restraint, about capturing the world as it is, or is it about expression, about shaping the world into what we want it to be? The answer, as always, depends on where one chooses to stand. But what is clear is that the phrase “I did it all in camera” now carries more weight — and more controversy — than ever before.

Sources:

Adobe Firefly AI.

DxO Labs, “DeepPRIME AI”.

Rethinking the Badge

Across nearly two centuries, the meaning of “doing it all in camera” has shifted again and again. In the nineteenth century, when photography was inseparable from chemistry, the phrase would have been meaningless: every image required intervention, and the badge of honour lay in mastering the entire chain of processes. In the Kodak era, when amateurs could simply press a button and send their film away, it became a mark of distinction for those who insisted on developing and printing their own work. In the twentieth century, the darkroom became a stage for artistry, and the badge was claimed both by purists who prized the decisive moment and by printers who transformed negatives into performances of light and shadow. In the digital age, the badge became a defensive gesture, a way of resisting the perceived excesses of Photoshop. And in the age of AI, it is both a rallying cry and a relic, invoked by those who resist automation and dismissed by those who embrace it.

What this history shows is that the badge has never been about truth in any absolute sense. Every photograph, from the daguerreotype to the digital composite, has been shaped by choices, interventions, and technologies. The claim to have “done it all in camera” has always been more symbolic than literal. It is a way of signalling values: discipline, restraint, authenticity, or, conversely, adaptability, creativity, and mastery of tools. The badge is less about what the photograph is than about what the photographer wants it to mean.

This is why the phrase has endured. It speaks to a deep human desire for authenticity, for the reassurance that what we are seeing is somehow “real.” It also speaks to the competitive nature of photographic culture, where claims of skill and purity are used to establish hierarchies of value. To say you did it all in camera is to draw a line between yourself and others — between the disciplined and the careless, the authentic and the artificial, the artist and the technician.

And yet, the badge has also been a moving target. Each new technology has redrawn the line between capture and process. What once seemed like cheating — roll film, enlargers, colour emulsions, digital sensors — has, in time, become accepted as part of the craft. It is likely that AI, too, will follow this trajectory. What feels like a rupture today may, in a generation, be seen as just another tool, no more controversial than autofocus or auto-exposure.

Perhaps, then, the real badge of honour has never been about where the work is done. It has been about understanding the process, making deliberate choices, and owning those choices. Whether in the camera, the darkroom, the lab, or the software suite, the skill lies not in purity but in intention. The question is not whether you did it all in camera, but whether you knew what you were doing, why you were doing it, and what you wanted the result to say.

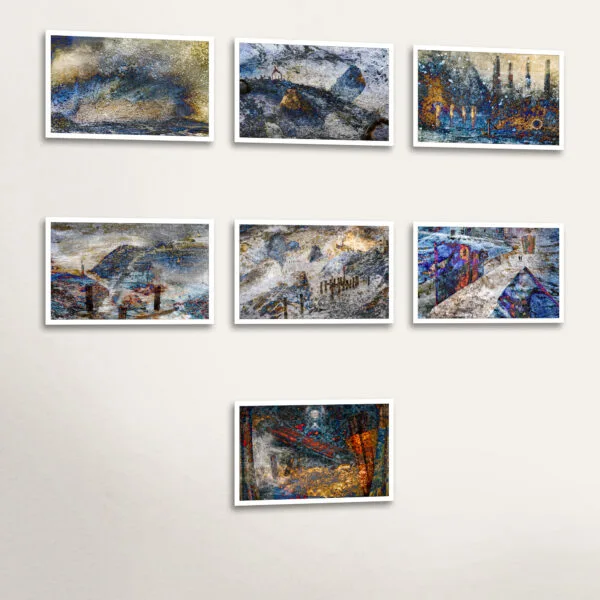

To rethink the badge is to recognise that photography has always been a hybrid medium, a negotiation between capture and interpretation. The badge of honour, if it exists at all, lies not in clinging to purity but in embracing responsibility. It lies in being able to say: this is my work, shaped by my choices, and I stand by it. That same spirit of intention runs through my own practice — for instance, in The Mariner’s Dreams series, where the interplay between capture and interpretation is not hidden but celebrated, inviting viewers to reflect on how images are made, and what they mean.

One Comment

This is a fascinating journey through the evolving meaning of “doing it all in camera”—but I wonder, do you think the badge of honour now says more about the photographer’s identity than about the truthfulness of the image itself? How do you personally balance authenticity and creativity in your own photographic practice?