Introduction

Every photographer, whether seasoned or just starting out, eventually bumps into the question of style. It’s the word that gets thrown around in galleries, in reviews, and in conversations between artists: What’s your style? For some, it’s a badge of honour — a shorthand for identity, a way of saying “this is me” without needing to explain further. For others, it’s a trap, a narrowing of possibilities that risks turning a living practice into a formula.

The idea of a “signature style” carries weight because photography is both art and craft. Unlike painting or sculpture, where the medium itself often dictates a certain look, photography is endlessly flexible. A single subject can be rendered in countless ways depending on choices of light, lens, framing, and post‑production. That flexibility makes the pursuit of a recognisable style both tempting and fraught.

Consider the way critics and historians often categorise photographers by style. Ansel Adams is remembered for his meticulous tonal control and large‑format landscapes of the American West (see The Ansel Adams Gallery archives). Henri Cartier‑Bresson is synonymous with the “decisive moment,” a phrase he himself popularised in his 1952 book Images à la Sauvette (published in English as The Decisive Moment). These examples show how style becomes shorthand for an entire career, even when the artist’s practice was more varied than the label suggests.

At the same time, style is not just about recognition; it’s about expectation. Audiences often want consistency. Collectors and publishers may prefer artists who can be “branded” by a particular look. Yet this expectation can be double‑edged. What begins as a strength can become a limitation, especially if the artist feels compelled to repeat themselves to meet external demand.

This week’s Friday Long Read asks whether mastering one style is the ultimate goal — the point at which a photographer can say they’ve arrived — or whether it’s a creative dead end, a cul‑de‑sac that leaves little room for growth. We’ll look at the arguments on both sides, drawing on examples from photographic history and contemporary practice, and we’ll consider the philosophical undercurrents that make this such a persistent debate.

The Case for Mastering One Style

For many photographers, the pursuit of a signature style feels like the natural end point of their journey. It’s the moment when experimentation gives way to clarity, when the scattered influences of early practice settle into something coherent. There are several reasons why this pursuit is seen as not only desirable but essential.

Recognition and Identity

A consistent style makes a photographer instantly recognisable. Steve McCurry’s saturated colours and human‑centred portraits are a case in point — his 1984 photograph Afghan Girl became one of the most iconic images of the 20th century, in part because it exemplified his distinctive palette and approach (National Geographic, 1985). Ansel Adams’ landscapes of Yosemite are so tightly bound to his name that they’ve become shorthand for a certain kind of photographic purity. Recognition at a glance is powerful: it allows an artist to stand out in a crowded field.

This recognition is not just about fame; it’s about trust. When audiences encounter a body of work that feels coherent, they are more likely to believe in the photographer’s vision. Cindy Sherman’s staged self‑portraits, for instance, became a recognisable brand in the art world, allowing her to build a career around a consistent conceptual framework (Museum of Modern Art archives).

Depth Over Breadth

Mastering one style allows for depth. Instead of skimming across multiple approaches, the photographer can dig into the nuances of a single aesthetic. Henri Cartier‑Bresson’s “decisive moment” philosophy, articulated in Images à la Sauvette (1952), is a clear example. By committing to this approach, he uncovered layers of meaning in everyday life that might have been missed with a more scattered practice.

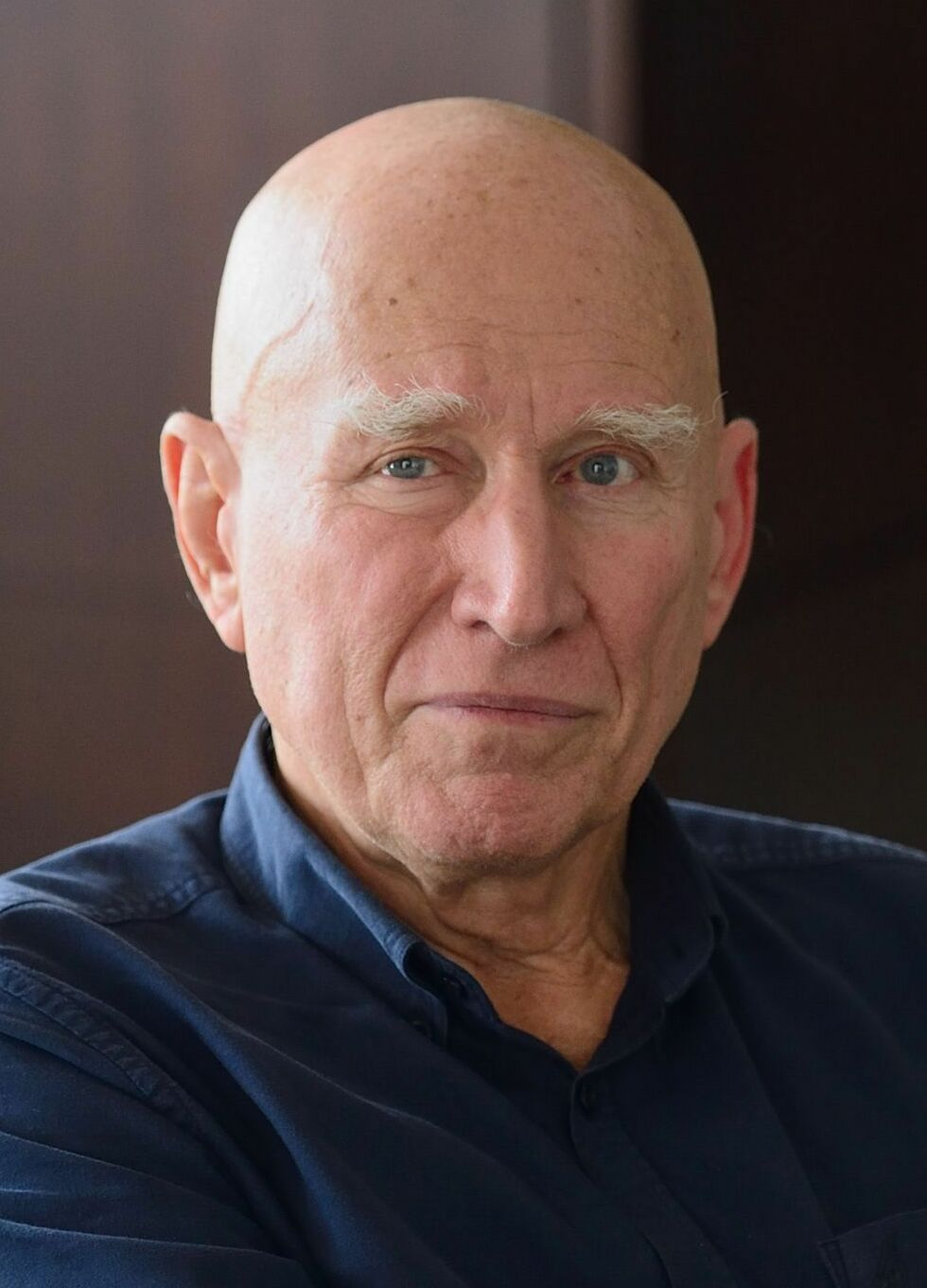

Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil, CC BY 3.0 BR, via Wikimedia Commons

Sebastião Salgado’s long‑term projects, such as Workers (1993) and Genesis (2013), show how sustained commitment to a particular visual language — stark black‑and‑white, monumental framing — can yield extraordinary depth. His style is not just a look; it is a way of seeing that shapes the meaning of his work.

William Eggleston’s colour photography provides another example. His saturated palette and democratic eye transformed everyday scenes into art, and by sticking to this approach, he was able to explore its nuances over decades. His style became a lens through which the banal was elevated, and his consistency allowed critics to trace the evolution of his vision.

Technical Anchors

Style is not only about subject matter or philosophy; it is also about technical choices. Format, focal length, lighting schema, colour management, and printing papers all contribute to recognisability. Adams’ use of large‑format cameras and the Zone System gave his work a distinctive tonal range. McCurry’s preference for Kodachrome film created a colour palette that became inseparable from his identity.

These technical anchors provide stability. They allow photographers to refine their craft within a consistent framework, producing work that feels coherent even as subjects change. For collectors and curators, this coherence is reassuring: it signals mastery and intentionality.

Marketability and Career Sustainability

From a practical standpoint, galleries, publishers, and collectors often prefer artists with a clear, identifiable style. It makes their work easier to categorise, promote, and sell. A photographer who has mastered one style can build a brand around it, which in turn supports career sustainability.

Art market reports consistently show that recognisability increases value. Collectors are more likely to invest in work that feels part of a coherent body, and galleries are more likely to represent artists who can be “branded” by a particular look (Art Market Report, 2020). This is not just about art; it’s about livelihood.

Historical Precedent

Art history is full of figures remembered for a distinct visual language. Claude Monet’s impressionist brushwork, Jackson Pollock’s drip technique, or Sherman’s staged personas — all are examples of artists who leaned into a recognisable style and became synonymous with it. Photography, as a younger art form, has inherited this expectation. The canon often privileges those who “own” a style, even if their practice was more varied than the label suggests.

The Comfort of Consistency

There’s also a psychological dimension. For both artist and audience, consistency can be comforting. The artist knows what they’re aiming for, and the audience knows what to expect. This predictability can build trust and loyalty, which in turn reinforces the artist’s position in the cultural landscape. Collectors often cite consistency as a reason for investing in an artist’s work — it reassures them that the artist has a clear vision and will continue to produce within that framework.

The Case Against Sticking to One Style

If a signature style can be a badge of honour, it can also become a straightjacket. The very consistency that makes a photographer recognisable can, over time, start to feel like repetition. There are several reasons why some artists resist the idea of settling into one aesthetic lane.

Risk of Repetition and Formula

Once a style is mastered, it can be tempting to repeat it endlessly. The danger is that the work begins to feel predictable, even mechanical. What was once fresh becomes formulaic. This is a criticism often levelled at commercial fashion photography, where a “look” can dominate for years until audiences tire of its predictability. Susan Sontag, in On Photography [paid link] (1979), warned that repetition risks turning images into clichés, stripping them of their original vitality.

Even celebrated fine‑art photographers have faced this critique. Andreas Gursky’s monumental, digitally manipulated images of global capitalism were ground-breaking in the 1990s, but some critics argue that later works felt like variations on a theme rather than fresh explorations. The danger of formula is that it can reduce art to a product line.

Changing Contexts

Photography doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Technology shifts, cultural tastes evolve, and new platforms emerge. A rigid adherence to one style risks leaving an artist behind.

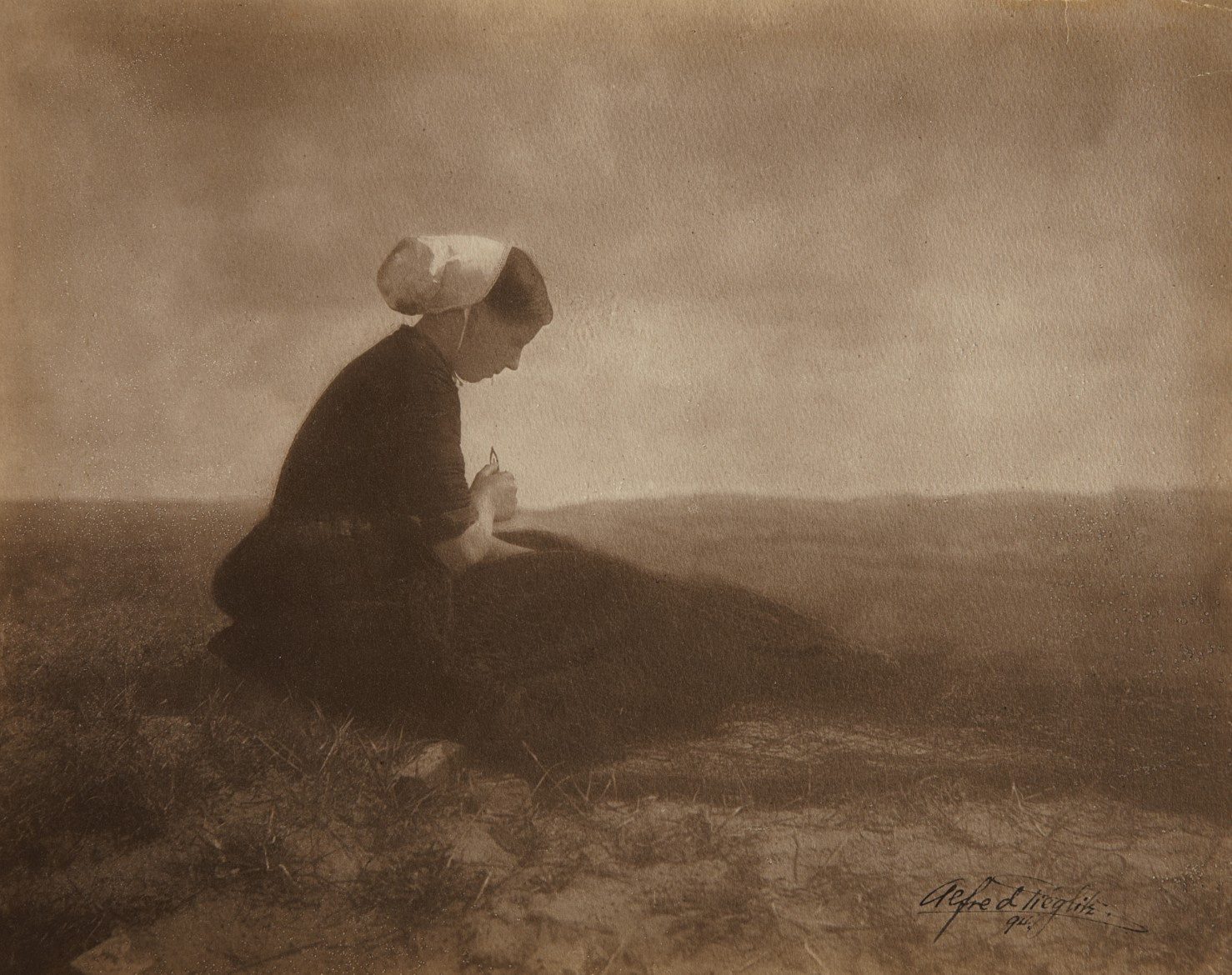

Consider the pictorialist style of the late 19th century, with its soft focus and painterly qualities. It was celebrated in its time, but quickly fell out of favour as modernist photographers like Paul Strand and Edward Weston pushed for sharpness and clarity (Camera Work archives, 1903–1917). What felt innovative in one era can seem outdated in another.

The same applies today. A style that relies heavily on analogue processes may be celebrated by purists, but risks marginalisation in a digital culture that prizes immediacy and accessibility. Conversely, a style built around Instagram‑friendly aesthetics may thrive now but could look dated in a decade.

Artistic Growth and Experimentation

Many artists argue that growth comes from experimentation. Trying different styles, techniques, and approaches keeps the practice alive. Pablo Picasso’s career is often cited here: his Blue Period, Rose Period, Cubism, and later works all show radical shifts in style, each opening new creative possibilities.

In photography, Nan Goldin’s refusal to be pinned down to a single aesthetic — moving from diaristic colour snapshots to large‑scale slide installations — demonstrates how fluidity can itself be a form of integrity. Similarly, Daido Moriyama’s gritty, high‑contrast street photography evolved into more experimental digital work in later years, showing that reinvention can be a form of survival.

Audience Expectations vs Artist’s Vision

Sometimes the pressure to maintain a style comes not from the artist but from the audience or market. Collectors, publishers, and even fans may want “more of the same.” But if the artist feels compelled to deliver consistency at the expense of exploration, the work risks becoming hollow.

Diane Arbus, for instance, became famous for her portraits of marginalised figures, but she often expressed frustration at being defined by that one approach (Diane Arbus: Revelations, 2003 [paid link]). Audience expectation can become a trap, where the artist is forced to repeat themselves to satisfy external demand rather than internal vision.

Style as Limitation

There’s a philosophical critique too: style can be seen as a limitation rather than a liberation. If every photograph must conform to a recognisable look, then the medium’s vast possibilities are narrowed. The artist may end up serving the style rather than using style to serve their vision.

Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida [paid link], suggested that the “punctum” of a photograph — the detail that pierces the viewer — often arises unexpectedly, outside of style. To insist on a fixed style risks missing those moments of serendipity.

Vilém Flusser, in Towards a Philosophy of Photography [paid link], argued that photographers must resist becoming “functionaries of the apparatus.” A rigid style can make the artist a servant of their own formula, rather than a free agent of creativity.

Contemporary Pressures

In the digital age, the pressure to maintain a consistent style is amplified by social media platforms. Instagram, for example, rewards visual consistency; photographers who maintain a “grid aesthetic” often gain more followers. Yet this can lead to formulaic repetition, where the pursuit of algorithmic approval overrides genuine exploration.

Lev Manovich’s Instagram and Contemporary Image (2017) argues that this has created a homogenisation of visual culture, with countless accounts mimicking the same pastel tones, minimal compositions, or cinematic colour grading. The danger is that style becomes conformity rather than individuality.

AI‑generated imagery adds another layer. With algorithms capable of producing “signature looks” at scale, the uniqueness of style is under threat. If a machine can replicate a photographer’s aesthetic instantly, then clinging to one style may no longer guarantee identity or originality.

Middle Ground Perspectives

The debate over style isn’t always a binary choice. Many photographers find themselves somewhere in between, navigating a path that allows for both consistency and evolution. This middle ground is often the most sustainable, balancing recognition with creative freedom.

Evolution Within a Style

A style doesn’t have to be static. It can evolve gradually, adapting to new influences, technologies, and contexts while retaining a recognisable core. Sebastião Salgado’s stark black‑and‑white documentary work is a good example: while his tonal language remains consistent, the themes of his projects have shifted from industrial labour (Workers [paid link], 1993) to untouched landscapes (Genesis [paid link], 2013). The style is recognisable, yet it grows with him.

William Eggleston’s colour photography also demonstrates this principle. His saturated palette and democratic eye transformed everyday scenes into art. Over decades, his work moved from snapshots of the American South to more complex explorations of place and mood, but the stylistic DNA remained intact. Evolution within a style allows artists to remain recognisable while avoiding stagnation.

Multiple Styles for Different Projects

Some photographers adopt different styles depending on the project. Annie Leibovitz is a prime example: her commercial portraits for Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone are polished, theatrical, and meticulously lit, while her personal work, such as Pilgrimage (2011), is quieter, more contemplative, and rooted in historical places. This duality allows her to maintain professional viability while keeping her creative practice fresh.

Alec Soth demonstrates a similar balance. His Sleeping by the Mississippi [paid link] (2004) established a recognisable style of large‑format, colour documentary, but later projects like Songbook (2014) shifted towards black‑and‑white and a more lyrical tone. The thread of identity remains, but the style flexes with the project.

My Own Practice as Case Study

My own practice offers a similar case in point. The Wingèd Beasties series, an open edition study of dragonflies and damselflies, is rooted in close observation and fine detail. Its style is crisp, intricate, and celebratory of natural form. By contrast, The Mariner’s Dreams, a limited edition series, inhabits a very different register: dreamlike, symbolic, and steeped in narrative suggestion. Each has its own integrity, yet together they demonstrate how distinct styles can coexist within a single body of work.

Far from undermining identity, this duality reinforces it. The shift between the two series shows that style can be project‑specific, chosen to suit subject and intent rather than imposed as a permanent signature. It’s a reminder that photographers need not be confined to one aesthetic lane; instead, they can allow style to flex and adapt, while still maintaining coherence across their wider practice.

Audience Perception vs Artist’s Intention

It’s worth noting that “signature style” is often imposed by critics, curators, or audiences rather than consciously chosen by the artist. Edward Weston is often remembered for his sharply focused still lifes of peppers and shells, but he also produced landscapes, nudes, and portraits. The audience tends to latch onto the most distinctive thread, even if the artist sees themselves as constantly evolving.

This tension between perception and intention is central to the middle ground. The artist may feel they are experimenting widely, but audiences may still perceive a consistent identity. In this sense, style is as much about reception as production.

Style as Foundation, Not Cage

One way to reconcile the tension is to treat style as a foundation rather than a prison. A recognisable style can provide stability and identity, but it doesn’t have to prevent exploration. It can be the starting point from which new experiments emerge, rather than the end point of a journey. Minor White encouraged his students to see style as a “vehicle” rather than a destination, arguing that it should serve the photographer’s vision rather than dictate it (Rites and Passages [paid link], 1978).

This perspective allows photographers to maintain coherence while embracing change. Style becomes a flexible framework rather than a rigid formula.

The Pragmatic Balance

Ultimately, many photographers balance the demands of recognition and marketability with the need for growth. They maintain enough consistency to be identifiable, but they allow themselves room to adapt. This pragmatic balance is often the most sustainable path, allowing artists to satisfy both their audiences and their own curiosity.

Practice Mechanics of Style

Style is often discussed in abstract terms — identity, recognition, philosophy — but underneath those ideas lies a set of practical mechanics. A photographer’s style is not just a matter of inspiration; it is built from repeatable decisions, technical anchors, and disciplined workflows. Understanding these mechanics reveals how style is sustained across projects, and how it can be adapted without losing coherence.

Intent‑Led Style Selection

Every project begins with intent. What is the subject, and what emotional register does it demand? A natural history series may call for precision and delicacy, while a conceptual body of work might lean towards atmosphere and symbolism. Style follows intent, not the other way around.

Technical Anchors

Style is sustained through technical anchors — the repeatable choices that create coherence. These anchors can include:

- Format discipline: Choosing a consistent camera format (large‑format, medium‑format, full‑frame digital) shapes the look of the work. Adams’ large‑format landscapes are inseparable from the tonal control of the Zone System.

- Lens selection: Focal length defines perspective. A photographer who consistently uses wide‑angle lenses will produce work with a recognisable spatial character.

- Lighting schema: Natural light vs. studio, hard vs. soft, directional vs. diffuse — these choices create a signature mood.

- Colour management: Film stock, digital profiles, LUTs, or presets all contribute to a consistent palette. McCurry’s Kodachrome colours are a classic example.

- Printing decisions: Paper stock, finishes, and tonal calibration affect how style is perceived in physical form. Glossy fibre prints emphasise detail; matte papers soften and diffuse.

These anchors are not rigid rules but repeatable systems. They allow photographers to refine their craft within a consistent framework, producing work that feels coherent even as subjects change.

Workflow Discipline

Style is also sustained through workflow discipline. Repeatable processes ensure that aesthetic decisions are not left to chance. This includes:

- Shooting routines: How locations are scouted, how subjects are approached, how exposures are metered.

- Editing pipelines: The sequence of adjustments in post‑production — contrast first, colour grading second, sharpening last — creates consistency.

- Sequencing and curation: The way images are selected and ordered in a series reinforces style. A photographer who favours quiet, contemplative pacing will sequence differently from one who favours dynamic contrasts.

Workflow discipline turns style from an idea into a practice. It ensures that the aesthetic is not just a one‑off but a sustained language.

Pivot Signals

At the same time, style must remain flexible. Projects sometimes resist the default look. Recognising when to pivot is part of the mechanics of style. Signals include:

- Subject resistance: If the subject feels diminished by the default style — for example, delicate insects flattened by harsh lighting — it may be time to shift.

- Emotional mismatch: If the mood of the project clashes with the established palette or tonality, the style must adapt.

- Audience fatigue: If viewers begin to perceive repetition, the artist may need to evolve.

Pivoting does not mean abandoning coherence. It means adjusting the mechanics to suit the project, while retaining enough invariants to maintain identity.

Coherence Rules

Even when styles shift, coherence can be maintained through invariants — the deeper fingerprints of the artist. These may include:

- Narrative stance: A commitment to empathy, curiosity, or irony that runs through all work.

- Ethical choices: Decisions about representation, consent, or truthfulness that remain constant.

- Compositional tendencies: A preference for symmetry, asymmetry, or negative space that persists across styles.

These coherence rules act as the glue between projects. They ensure that even when the visual language changes, the authorial voice remains recognisable.

Audience Conditioning

Style is not only produced; it is received. Audiences often expect consistency, and sudden shifts can be disorienting. Conditioning the audience for change is part of the mechanics of style. This can be done through:

- Previews and process notes: Sharing works‑in‑progress or behind‑the‑scenes insights prepares audiences for evolution.

- Sequencing stylistic shifts: Introducing new aesthetics gradually, so they feel like evolution rather than rupture.

- Contextual framing: Explaining why a new style was chosen — linking it to subject, intent, or philosophy — helps audiences understand the change.

This conditioning allows photographers to evolve without losing trust. It turns stylistic shifts into part of the narrative rather than a break in continuity.

Case Studies in Practice

Several photographers illustrate these mechanics in action:

- Ansel Adams: His style was anchored in large‑format cameras, the Zone System, and meticulous printing. These technical anchors created coherence across decades.

- Nan Goldin: Her diaristic snapshots were sustained by a consistent workflow — intimate access, colour film, flash lighting — but she pivoted into slide installations when the subject demanded a new form.

- Alec Soth: His project‑based approach shows how style can flex while coherence rules remain. Large‑format discipline and empathetic narrative stance tie his work together, even as colour shifts to black‑and‑white.

These examples show that style is not just an abstract identity but a set of practical mechanics that can be repeated, adapted, and evolved.

Closing Thought

Style is not just an idea; it is a practice. It is built from intent, sustained through technical anchors and workflow discipline, adapted through pivot signals, and maintained through coherence rules. It is negotiated with audiences, conditioned through framing, and illustrated in case studies.

Understanding these mechanics reveals that style is not a cage but a toolkit — a set of repeatable decisions that can be deployed, adjusted, and evolved. Mastery lies not in freezing style but in knowing how to use its mechanics to serve vision.

Philosophical Considerations

The debate over style isn’t just about branding or technique; it touches on fundamental questions about what it means to be an artist. Philosophers, critics, and photographers themselves have wrestled with the tension between coherence and freedom, between identity and evolution.

Style as Compass vs Cage

Style can be seen as both compass and cage. As a compass, it provides direction, guiding the photographer towards coherence and clarity. As a cage, it restricts movement, locking the artist into a narrow set of possibilities. Susan Sontag, in On Photography [paid link] (1979), warned that style can become “mannerism,” a hollow repetition of gestures. Yet she also acknowledged that style is unavoidable — every choice of framing, light, or subject is already a stylistic decision.

This paradox means that style is both liberating and limiting. It can help an artist find their voice, but it can also trap them in a loop of self‑imitation.

The Question of Identity

Style is often equated with identity: “this is who I am as an artist.” But identity itself is fluid. John Berger, in Ways of Seeing [paid link] (1972), emphasised that perception is shaped by context — what we see is never fixed, but always influenced by culture, history, and personal experience. If identity is fluid, then insisting on a single style may deny the natural evolution of selfhood.

A photographer’s style might therefore be less a fixed identity than a snapshot of their vision at a particular moment in time. To freeze style is to freeze identity, which risks denying the artist’s own growth.

Photography’s Dual Nature

Photography complicates the question further because it straddles art and documentation. A painter can invent a world entirely from imagination, but a photographer is always working with something that exists. Does this make style less important, since the subject itself carries weight? Or does it make style more important, since it’s the photographer’s choices that transform documentation into art?

Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida [paid link], distinguished between the studium (the cultural, coded aspect of a photograph) and the punctum (the detail that pierces the viewer). Style often belongs to the studium — the recognisable look — but the punctum may arise outside of style, in unexpected details. This suggests that style can frame meaning but cannot fully control it.

Originality and Influence

No style exists in isolation. Every aesthetic choice is shaped by influences — teachers, peers, cultural trends, even accidents. Walter Benjamin, in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936), argued that reproducibility changes the aura of art, making style both more accessible and more vulnerable to imitation.

To claim a “signature style” is to claim originality, but originality itself is always entangled with what came before. Style may be less about ownership than about fluency in a shared visual language. The artist speaks that language in their own accent, but the words are not entirely theirs.

The Pursuit of Mastery

Does mastering a style mean reaching an endpoint, or is mastery simply another stage in an ongoing journey? Minor White suggested that style should be seen as a “vehicle” rather than a destination, a way of moving towards vision rather than a final resting place (Rites and Passages [paid link], 1978).

Vilém Flusser, in Towards a Philosophy of Photography [paid link] (1983), warned that photographers risk becoming “functionaries of the apparatus,” repeating formulas dictated by technology. Mastery, in this sense, is not about perfecting a style but about resisting automation — keeping the practice alive by questioning its own habits.

Contemporary Reflections

In today’s photographic culture, style is often discussed in terms of “brand.” Social media platforms encourage consistency, rewarding photographers who maintain a recognisable aesthetic across their feeds. Yet this raises philosophical questions: is style being pursued for artistic reasons, or for algorithmic visibility?

Lev Manovich’s Instagram and Contemporary Image (2017) suggests that the homogenisation of visual culture is a direct result of these pressures. The philosophical challenge, then, is whether style remains a tool for expression or becomes a tool for conformity.

Market and Cultural Pressures

Style is never formed in isolation. Even the most personal aesthetic choices are made within a wider cultural and economic ecosystem. Photographers may feel they are simply following their own vision, but the market, institutions, and audiences exert powerful pressures that shape what styles thrive, which fade, and how they are remembered.

Collector Psychology

Collectors often value recognisability. A body of work that feels coherent reassures them that the artist has a clear vision and will continue to produce within that framework. This predictability makes investment safer. In art market reports, consistency is frequently cited as a factor in pricing stability. A collector who buys a print today wants to feel confident that the artist’s future work will not diverge so radically that the earlier piece feels anomalous.

This psychology can encourage photographers to maintain a signature style even when they feel the urge to experiment. The market rewards coherence, but coherence can become conformity. Artists must decide whether to prioritise collector confidence or personal growth.

Gallery and Institutional Framing

Galleries and museums also play a role in shaping style. When curators mount retrospectives, they often emphasise the most distinctive thread in an artist’s practice, even if the artist worked in multiple styles. This framing can cement a particular look as the “signature style,” regardless of the artist’s own intentions.

For example, Edward Weston is often remembered for his sharply focused still lifes of peppers and shells, but he also produced landscapes, nudes, and portraits. The canon privileges the most distinctive thread, narrowing the perception of his style. Institutions thus shape not only how audiences see an artist’s work but also how artists see themselves.

Platform Effects

In the digital age, platforms exert enormous influence on style. Instagram, TikTok, and online galleries reward visual consistency. Photographers who maintain a recognisable “grid aesthetic” often gain more followers, while those who experiment widely may struggle to build an audience.

This algorithmic pressure can lead to homogenisation. Lev Manovich’s Instagram and Contemporary Image (2017) argues that the platform has created a global visual vernacular: pastel tones, minimal compositions, cinematic colour grading. What began as individual stylistic choices has become conformity, driven by the pursuit of visibility.

The danger is that style becomes less about artistic intent and more about platform optimisation. Photographers may find themselves serving algorithms rather than vision, repeating looks that perform well rather than exploring new possibilities.

Historical Shifts

Markets have always responded to stylistic change, sometimes embracing it, sometimes resisting. The decline of pictorialism and the rise of modernism in the early 20th century illustrate how cultural tastes can shift rapidly. Soft‑focus, painterly photographs were celebrated in their time, but as modernist photographers like Paul Strand and Edward Weston pushed for sharpness and clarity, pictorialism was dismissed as outdated.

Similarly, the embrace of colour photography in the 1970s marked a cultural shift. William Eggleston’s Guide (1976) was initially controversial — critics dismissed colour as vulgar or commercial — but it eventually redefined the medium. Markets and institutions that once resisted colour came to celebrate it, proving that stylistic shifts can reshape cultural value.

Contemporary Challenges: AI and Reproducibility

Today, AI‑generated imagery adds a new layer of pressure. Algorithms can replicate “signature looks” at scale, eroding the uniqueness of style. If a machine can produce images that mimic a photographer’s aesthetic instantly, then recognisability may no longer guarantee identity or originality.

Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936) argued that reproducibility changes the aura of art. In the age of AI, this argument becomes even more urgent. Style can be copied, remixed, and mass‑produced, raising questions about authorship and authenticity. Photographers must decide whether to double down on recognisability or embrace fluidity as a defence against imitation.

Audience Expectations

Audiences also exert pressure. Fans often want “more of the same,” and sudden stylistic shifts can be disorienting. This expectation can trap artists in repetition, forcing them to deliver consistency at the expense of exploration. Yet audiences can also be conditioned to accept change. By framing stylistic evolution as part of the narrative, photographers can bring their audiences along for the journey.

The tension between audience expectation and artistic vision is central to the mechanics of style. Artists must negotiate between satisfying external demand and pursuing internal curiosity.

The Economics of Risk

Underlying all these pressures is the economics of risk. Style is not just an artistic choice; it is a financial one. Consistency reduces risk for collectors, galleries, and platforms. Experimentation increases risk but may yield greater rewards in the long term.

Photographers must decide how much risk they are willing to take. Some prioritise stability, maintaining a recognisable style to secure livelihood. Others embrace risk, reinventing themselves even if it means losing short‑term support. The market rewards both strategies at different times, but the balance is precarious.

Style as Negotiation

Ultimately, style is a negotiation between artist and world. It is shaped by collector psychology, institutional framing, platform effects, historical shifts, technological challenges, and audience expectations. Photographers may feel they are simply following their own vision, but that vision is always mediated by external forces.

Recognising these pressures does not mean surrendering to them. It means understanding the ecosystem in which style operates. Mastery of style is not just about internal coherence; it is about navigating external demands without losing integrity.

Closing Thought

Style is not only an artistic identity but also a cultural currency. It is traded in markets, framed by institutions, rewarded by platforms, and shaped by audiences. Photographers who master style must therefore master negotiation — balancing coherence with flexibility, recognition with growth, and external pressures with internal vision.

In this sense, style is both personal and collective. It belongs to the artist, but it also belongs to the world that receives, rewards, and remembers it.

Conclusion

The question of whether mastering one signature style is the ultimate goal or a creative dead end doesn’t yield a simple answer. For some photographers, style is the anchor that gives their work coherence, recognition, and longevity. For others, it is a constraint that risks turning art into repetition.

We’ve seen how a single style can provide depth, identity, and marketability, but also how it can limit growth, feel outdated, or become a cage imposed by audience expectations. The middle ground offers a pragmatic balance: style as foundation rather than prison, a recognisable thread that evolves over time or coexists with other approaches.

Philosophers and critics remind us that style is both unavoidable and unstable. Every choice of framing, light, or subject is already a stylistic decision, yet identity itself is fluid. To insist on one fixed style may deny the natural evolution of selfhood. Photography’s dual nature — art and documentation — complicates matters further, since style can both elevate and obscure the subject.

My own practice illustrates this tension. The Wingèd Beasties series, with its intricate celebration of dragonflies and damselflies, speaks in a language of precision and natural detail. The Mariner’s Dreams, by contrast, inhabits a dreamlike register, full of symbolism and narrative suggestion. Each series has its own distinct style, yet neither cancels out the other. Together they remind me that style is not a cage but a set of possibilities. Sometimes the work demands delicacy, sometimes atmosphere, and sometimes something else entirely.

So perhaps the question isn’t whether mastering one style is the goal or a dead end, but whether we allow style to serve our vision rather than dictate it. Mastery can be a milestone, a point of clarity, but it need not be the end of the journey. The real danger lies not in having a style, but in letting it silence curiosity.

3 Comments

Have you ever found that developing a strong personal style in your photography has helped you grow, or do you feel it sometimes makes you hesitant to try something new? I’m curious—how do you balance consistency with creative exploration in your own work?

I think you should call this the ‘weekend long read’ Paul. Lol.

They’re certainly not for anyone who is in a hurry. 🙂