Early Life and Education

René François Ghislain Magritte was born in 1898 in Lessines, Belgium, the eldest of three brothers. His childhood was marked by both creativity and tragedy: his mother’s death when he was thirteen left a profound emotional imprint. Some scholars suggest that the recurring motifs of veils, concealment, and mystery in his paintings may trace back to this early trauma.

Magritte studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918, where he encountered Cubism and Futurism. Yet he quickly grew dissatisfied with academic conventions. Instead, he gravitated toward the Surrealist movement, which sought to unlock the unconscious mind and challenge rationality. Unlike many of his Parisian peers, Magritte remained in Brussels for most of his life, living quietly with his wife Georgette. This contrast between his ordinary domestic life and the strangeness of his art only heightened the intrigue surrounding his work.

Magritte and the Surrealist Movement

Magritte joined the Surrealists in the 1920s, but his approach was distinct. While Salvador Dalí painted melting clocks and dreamscapes, Magritte’s genius lay in the subtle estrangement of the everyday. He took familiar objects—an apple, a pipe, a bowler hat—and placed them in uncanny contexts. His works are not fantastical escapes but philosophical provocations, asking us to question what we see and how we interpret it.

He once remarked: “Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see.” This paradox became the foundation of his art.

Key Works and Themes

Magritte’s oeuvre is vast, but several works stand out as touchstones:

- The Treachery of Images (1929): A pipe with the caption “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”). It forces us to confront the difference between an object and its representation.

- The Lovers (1928): Two figures kiss through veils of cloth, evoking intimacy and alienation simultaneously.

- The Son of Man (1964): A man in a bowler hat with his face obscured by a hovering green apple—perhaps his most iconic image.

- Golconda (1953): A sky filled with bowler‑hatted men raining down like raindrops, blurring individuality into pattern.

- The False Mirror (1929): A giant human eye with a sky reflected in its iris, suggesting that perception itself is a surreal act.

- The Human Condition (1933): A painting within a painting, where a canvas placed before a window perfectly continues the landscape behind it, collapsing reality and representation.

These works reveal recurring themes: concealment, repetition, the instability of perception, and the tension between reality and illusion.

Influence on Modern and Contemporary Art

Magritte’s influence has been profound. Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein admired his bold, graphic clarity. Conceptual artists drew inspiration from his philosophical wit. His imagery has appeared in advertising, cinema, and fashion, yet it never loses its enigmatic power. Filmmakers such as David Lynch and the Coen Brothers have echoed his unsettling juxtapositions, while contemporary artists continue to borrow his visual language.

By the 1960s, Magritte was already world‑famous, his paintings reproduced in posters and book covers. Yet their mystery endures: they are not puzzles to be solved, but experiences to be lived.

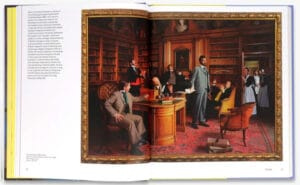

An Homage: The Sun of Man

Magritte’s visual language continues to inspire artists across disciplines—including my own work, The Sun of Man. This piece unfolds as a surreal landscape of apples stretching into the horizon, an impossible orchard that nods directly to Magritte’s fascination with repetition and scale. On a distant rise, a couple embrace with their heads veiled in cloth, echoing The Lovers while emphasising both intimacy and isolation.

At the centre, a barren tree entangled with fabric suggests the complexities of human connection. Above it all, a glowing light bulb crowned with a bowler hat presides like a whimsical, dreamlike sun—a celestial transformation of Magritte’s The Son of Man. The composition balances playfulness with poignancy, suggesting that love and existence are always set against forces larger than ourselves.

You can explore the work in detail here: The Sun of Man.

Why Magritte Still Matters

In our image‑saturated age, Magritte’s art feels more relevant than ever. His paintings remind us that seeing is not a passive act but an active, interpretive process. By disrupting the ordinary, he opens space for wonder, humour, and reflection.

Magritte once said: “Art evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist.” That mystery is what continues to draw us to his work—and what inspired me to create The Sun of Man, a piece that both honours and reimagines his enduring legacy.

One Comment

Magritte often blurred the line between reality and illusion in his paintings—do you think his focus on ordinary objects in strange settings changes how you view everyday life, or does it simply make you question what’s real and what isn’t?