From Model to Master Photographer

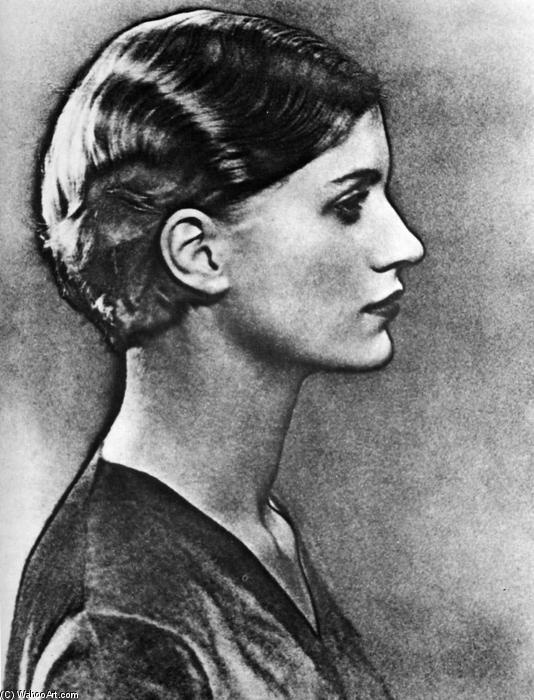

For decades, the name Lee Miller has been inextricably linked to the men in her orbit: the luminous muse to Man Ray, the subject for Picasso. But a landmark new retrospective at Tate Britain is determined to shift the focus, finally granting her the recognition she deserves as a formidable artist in her own right. Her journey from Vogue cover model to a photographer who stared into the heart of 20th-century darkness is one of the most extraordinary in modern art.

More Than a Muse: The Surrealist Collaborator

Miller’s story often begins in Paris, 1929. Arriving from New York with the ambition to become Man Ray’s pupil, she was swiftly told he didn’t take students. Undeterred, she soon became his lover, collaborator, and creative equal. The iconic, solarised portraits Ray took of her are masterpieces of Surrealist photography, but as the Tate exhibition makes clear, Miller was far from a passive subject. She was a co-creator, performing for the camera with a skill honed by her training in theatre and dance.

The show explores the idea that it was actually Miller who accidentally discovered the solarisation technique, a process that lends the images their ethereal, otherworldly glow. This challenges the traditional narrative of the lone male genius, suggesting instead a dynamic partnership where ideas flowed freely. As Miller herself recalled, she and Ray “were like one person when we were working.”

Confronting the Abyss: The War Photographer

Miller’s most profound transformation came with the outbreak of the Second World War. She became an official war correspondent for Vogue, embedding with the US troops. Her mission was to “document war as historical evidence,” and she did so with unflinching courage. She was present at the liberation of the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps, images from which remain some of the most harrowing records of the Holocaust.

One of her most chilling works is a diptych from Leipzig in 1945. The first image, ‘The Deputy Bürgermeister’s Daughter’, shows a young girl, angelic in sleep, on a sofa. The companion photograph reveals the horrific truth: her family lies dead around the room, having taken cyanide. This brutal clarity, forcing the viewer to confront the human cost of war from ‘the other side’, is a testament to Miller’s immense strength and her commitment to truth.

It was in this period that she created one of the war’s most symbolic images, captured not by her but of her. In a famous photograph by David E. Scherman, Miller is seen bathing in Hitler’s tub in Munich, her muddy boots staining his bathmat, on the very day he died in Berlin. The image is a powerful act of defilement and reclamation.

A Legacy Reclaimed

After the war, the trauma of what she had witnessed took its toll. Miller largely retreated from photography, turning her immense creativity towards culinary arts at her home in East Sussex with her husband, Roland Penrose. For years, her vast photographic archive—some 60,000 negatives—remained hidden in the attic, only rediscovered by her son, Antony Penrose, after her death in 1977.

It is largely thanks to his efforts that we can now appreciate the full scope of her genius. This exhibition is not just a celebration of a life of glamour and surreal happenstance, but a sober acknowledgement of an artist who used her lens to explore every facet of the human experience, from the dreamlike to the devastating.

Miller’s ability to find a stark, arresting composition, whether in the deserts of Egypt or the ruins of Europe, speaks to a unique photographic eye. For those inspired by powerful imagery that captures a moment and tells a deeper story, I find that fine art photography can bring a similar narrative depth into your home. If you are looking for a contemporary photographic artwork that evokes a sense of myth and memory, you might explore pieces from The Mariner’s Dreams series in my own shop.

‘Lee Miller’ is on at Tate Britain from 2 October 2025 to 15 February 2026.