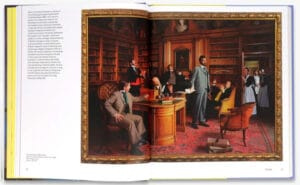

More Than a Picture: The Camera’s Role in Colonial Ambition

From its very inception, photography was more than just a tool for capturing light; it was an instrument of power. In the mid-19th century, as Western European nations vied for control over vast swathes of North Africa and Asia, the camera became an indispensable companion to the soldier, the cartographer, and the administrator.

The seemingly innocent subjects of landscapes, ancient monuments, and foreign architecture were not chosen at random. They were deliberate records of possession, shaping a narrative of empire for audiences back home. These images reassured the metropolitan public that their governments were not only expanding territory but also “civilising” and cataloguing the world.

British photographers were at the forefront of this colonial documentation. Adventurers like Francis Frith, with his meticulously composed albums of Egypt and Asia Minor, and Samuel Bourne, who traversed the Indian subcontinent with a full retinue of assistants, produced images that were consumed with fascination. Their photographs presented a curated vision of distant lands—often portrayed as ancient, mysterious, and ripe for Western stewardship. They served to map, to classify, and ultimately, to claim.

For further reading:

- Photography and Colonialism – Decolonial Centre

- What is colonial about colonial photographs? – photoCLEC

A Legacy in Light and Shadow

This colonial history is a complex and crucial chapter in the story of photography. It reminds us that every image is framed not just by a viewfinder, but by the intentions and ideologies of its creator. The lens was never truly neutral.

A photograph could capture the beauty of a monument while erasing the contemporary people and cultures surrounding it, reducing living, breathing lands to silent, picturesque possessions. The “timeless” quality of these images was often a deliberate construction, stripping away signs of modernity to reinforce the idea of the colonised world as static, awaiting Western intervention.

Today, we can look back on this era with a more critical eye, appreciating the technical skill of these early photographers while also acknowledging the problematic context of their work. It prompts us to consider how modern photographers approach their subjects, especially when dealing with history, place, and culture. The power to frame a narrative through an image remains as potent as ever.

For critical perspectives:

- Photoanthropocene: The Decentered Lens of Colonial Photography (PDF)

- Confronting the Coloniality and Credibility of the Camera – Harvard Art History Journal

Architecture Through a Contemporary Lens

This historical relationship between photography and the built environment is something I find endlessly fascinating. While the colonial photographers documented architecture to showcase imperial reach, contemporary artists often explore structures to reveal their inherent beauty, drama, and the stories etched into their surfaces.

It’s a shift from documentation as possession to interpretation as appreciation. Where once the photograph was a ledger of conquest, today it can be a meditation on memory, space, and identity.

If you are drawn to the powerful interplay of structure, light, and history, I invite you to explore a modern perspective in my Architecture Collection. Here, you will find monochrome artworks that celebrate the quiet poetry of the built environment, transforming familiar spaces into moments of deep contemplation.

Owning a Piece of the Story

The history of photography is a tapestry woven with many threads—technical innovation, artistic expression, and, as we’ve seen, political power. By understanding this past, we can engage with photography in a more meaningful way today.

Whether you are a history enthusiast or an art lover, owning a fine art print allows you to be part of this ongoing story. Each piece is not just a decoration, but a conversation with the rich and complex legacy of the image.

For broader context:

Beyond the Frame

When you look at a photograph of a historic place, do you see it as a document, a story, or a claim?

One Comment

How do you think the legacy of colonial-era photography still influences the way I—and others—view images of historic architecture or distant places today?