Introduction – What Do We Mean by Commodification?

When we talk about commodification in art, we are really asking what happens when something created for expression, reflection, or beauty becomes a product to be bought and sold. This is not a new question, but in photography—and especially in photographic art—it has always carried a sharper edge. Unlike painting or sculpture, a photograph can be reproduced endlessly. That reproducibility is both its strength and its weakness: it allows images to circulate widely, but it also raises doubts about whether a print can ever be “unique” in the way a canvas or carved stone might be.

Yet when we shift the focus from “pure” photography to photographic art, the question becomes more nuanced. Photographic art is not simply about capturing a scene or documenting reality. It is about interpretation, construction, and the deliberate shaping of visual experience. A photographic artwork may involve complex staging, digital manipulation, or a conceptual framework that transforms the image into something more than a record. In this context, the reproducibility of the medium is not the whole story. What matters is the intentionality behind the work—the fact that the artist has chosen to present a particular image in a particular way, often as part of a series or narrative. The print becomes not just a copy, but a manifestation of artistic vision.

For some, commodification feels like a betrayal of photography’s democratic spirit. If anyone can own a copy, why should scarcity be imposed? Photography, they argue, was born as a medium of accessibility, allowing images to be shared across social classes and geographies. To restrict that openness by limiting editions or inflating prices seems to contradict its essence. In this view, commodification risks turning photographs into luxury goods, stripping them of their cultural reach.

For others, commodification is the very thing that elevates photography into the realm of fine art. Without scarcity, prints risk being seen as disposable, no different from posters or postcards. A photographic artwork, they argue, deserves to be treated with the same respect as a painting or sculpture. Scarcity signals intentionality: it tells the collector that this print is not just another mechanical copy, but part of a carefully curated body of work. In this sense, commodification is not about exclusion, but about meaning.

The tension lies in whether commodification diminishes meaning or enhances it. Does limiting editions undermine photography’s democratic roots, or does it protect the integrity of photographic art in a world flooded with images? Is scarcity an artificial imposition, or a necessary marker of value? These are not easy questions, and they have been debated for more than a century.

This essay will explore both sides of that debate. We will look at the history of photographic prints, the arguments against turning them into commodities, and the reasons why scarcity has become central to their value. Along the way, we will consider whether limited editions offer a middle ground—one that respects photography’s reproducibility while still giving collectors something rare and intentional. And because our focus is on photographic art rather than “pure” photography, we will ask whether commodification might actually be the mechanism that allows photographic art to be recognised, preserved, and valued alongside other forms of fine art.

A Brief History of Photographic Prints

Photography has always carried with it the paradox of reproducibility. From its earliest days in the 19th century, the medium was celebrated for its ability to capture and share images widely. Daguerreotypes, introduced in 1839, produced unique images on silvered copper plates—each one singular, unable to be duplicated. At the same time, William Henry Fox Talbot’s calotype process (patented in 1841) allowed for multiple prints from a single negative, setting the stage for photography as a medium of mass reproduction.

This tension between uniqueness and reproducibility shaped the way photography was understood. Painters and sculptors could claim originality in every brushstroke or chisel mark, but photographers faced the challenge of proving that their work was more than a mechanical copy. The question was not only technical but philosophical: could a medium defined by reproducibility ever achieve the aura of singularity that defined traditional art forms?

By the early 20th century, photographers began signing prints and producing limited runs as a way to assert artistic value. The practice was not universal—many resisted it—but it became a recognised strategy for elevating photography to the level of fine art. A signed print was no longer just a photograph; it was a statement of authorship, a way of saying that this particular object carried the artist’s intention. In the realm of photographic art, this distinction mattered. A print was not simply a record of light and shadow; it was a crafted artefact, part of a larger vision.

The philosopher Walter Benjamin famously addressed this issue in his 1935 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. He argued that reproducibility stripped art of its “aura”—the unique presence tied to a specific time and place. Photography, by its very nature, seemed to lack this aura. Yet Benjamin also suggested that reproducibility could democratise art, making it accessible to wider audiences. For photographic art, this paradox was particularly acute: how could artists preserve the aura of their work while embracing the democratic potential of the medium?

Throughout the 20th century, photographers navigated this divide in different ways. Some, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, resisted the idea of limited editions, preferring to let their images circulate freely. His approach reflected a belief in photography as a universal language, a medium that should not be constrained by scarcity. Others, such as Ansel Adams, embraced the notion of commodification, producing signed prints that later commanded high prices at auction. For Adams, the print was not just a reproduction but a crafted object, carefully controlled in its tonal range and presentation. His limited editions were a way of asserting that photography could stand alongside painting and sculpture as fine art.

By the late 20th century, limited editions had become a standard practice in fine art photography. Galleries and collectors expected them, and photographers who resisted often found themselves outside the commercial mainstream. The print was no longer just a photograph—it was a commodity, shaped by scarcity, signature, and provenance. For photographic artists, this shift was significant. It meant that their work could be valued not only for its imagery but for its intentionality, its place within a curated body of art. The limited edition became a marker of seriousness, a way of distinguishing art from mass culture.

This history shows how the paradox of reproducibility has been negotiated over time. From the singular daguerreotype to the endlessly reproducible digital file, photography has always wrestled with questions of uniqueness and value. Limited editions emerged as one solution, a way of preserving aura in a medium defined by mechanical reproduction. For photographic art, they remain a crucial tool—balancing accessibility with exclusivity, and ensuring that prints are recognised not just as images, but as intentional works of art.

Arguments Against Commodification

One of the strongest arguments against commodifying photographic prints is that it undermines the democratic spirit of photography. From its earliest days, photography was celebrated as a medium that could be shared widely, reproduced easily, and accessed by people who might never own a painting or sculpture. It was, in many ways, the great leveller of the visual arts: a technology that allowed images to circulate beyond the walls of galleries and private collections. To impose scarcity on something inherently reproducible feels, to some critics, like a contradiction in terms.

Unlimited prints, they argue, preserve the “truth” of photography. A negative or digital file can produce countless identical images, and that reproducibility is part of what makes photography unique. Restricting editions, or artificially limiting supply, risks turning photographs into investment objects rather than cultural artefacts. In this view, commodification strips photography of its openness and reduces it to a market transaction. The photograph ceases to be a shared cultural record and becomes instead a token of exclusivity.

This concern is particularly sharp when we consider photographic art. Unlike documentary photography, which often aims to record reality, photographic art is about interpretation, construction, and deliberate vision. Yet even here, critics argue, the imposition of scarcity risks distorting the meaning of the work. If a print is valued primarily because it is rare, then its artistic significance may be overshadowed by its market value. The collector’s desire for possession can eclipse the audience’s engagement with the image itself.

There’s also the social dimension. Commodification privileges wealth over appreciation. If prints are scarce and priced accordingly, only a small group of collectors can participate. Photography then risks losing its democratic reach, becoming the preserve of those who can afford to buy into exclusivity. This echoes broader debates in the art world about accessibility versus elitism. Should art be available to all, or should it be reserved for those who can pay for rarity? For critics of commodification, the answer is clear: photography’s strength lies in its openness, and limiting editions undermines that.

Some photographers have resisted commodification for precisely these reasons. Margaret Bourke‑White, one of LIFE magazine’s pioneering photojournalists, created her work with the explicit aim of circulation. Her images were designed to reach millions of readers, not to be restricted by scarcity. Bourke‑White’s approach reflected a belief that photography should remain a medium of mass communication and cultural record, not a luxury commodity. For her, the power of photography lay in its ability to inform, inspire, and connect across boundaries. To limit that circulation would have been to betray the essence of the medium.

Finally, there is the philosophical objection. Commodification risks reducing art to its monetary value. When prints are bought and sold primarily as investments, their meaning as works of expression or cultural record can be overshadowed. Critics argue that this distorts the relationship between artist and audience, replacing engagement with speculation. The photograph becomes less a site of reflection and more a financial instrument. In this view, commodification erodes the authenticity of photographic art, turning it into a commodity stripped of its cultural resonance.

These arguments remind us that commodification is not a neutral practice. It shapes how photography is understood, who has access to it, and what it means to own a print. For those who value photography’s democratic spirit, limited editions can feel like an imposition—an artificial scarcity that undermines the openness of the medium. Whether one agrees with this critique or not, it is a perspective that must be taken seriously, especially when considering the place of photographic art in contemporary culture.

Arguments For Commodification

If the critics of commodification see scarcity as a betrayal of photography’s democratic spirit, its defenders argue almost the opposite: that commodification is what gives photography its rightful place in the hierarchy of art. Without scarcity, a print risks being seen as little more than a poster—something endlessly reproducible, and therefore disposable. By introducing limits of some kind, photographers signal that their work is not just another image, but a crafted object with intention behind it. This distinction becomes even more important when we talk about photographic art, where the print is not simply a record of reality but a carefully constructed artefact, shaped by vision, technique, and narrative.

Scarcity creates value. Collectors are reassured that what they own is not diluted by thousands of identical copies circulating in the market. Rarity has always been a marker of cultural worth, and in photography it can be expressed in different ways: through signed prints, unique printing processes, carefully controlled runs, or distinctive provenance. These signals of scarcity elevate photography into the same cultural space as painting or sculpture, both of which rely on uniqueness to command attention. In this sense, commodification is not a betrayal of photography’s reproducibility, but a way of ensuring that photographic art is recognised as intentional creation rather than mere duplication.

There is also the matter of connection. Collectors often seek more than just an image; they want a tangible link to the artist’s vision. A print that carries the artist’s signature, or is known to be part of a carefully managed body of work, provides that link. It tells the collector that the artist has chosen to make this particular object part of their practice, and that it carries a deliberate place in the narrative. In photographic art, this connection is especially significant. The print is not just a copy of a file; it is a chosen manifestation of the artist’s vision, often produced with specific materials, papers, and processes that reinforce its meaning. To own such a print is to participate in the artist’s practice, to hold a piece of their intentionality in physical form.

Examples abound of how scarcity has shaped value. Ansel Adams’ prints, for instance, have fetched high prices at auction not only because of their beauty but because of their rarity and provenance. Adams was meticulous in his printing, often producing small runs with careful tonal control. The scarcity of these prints reinforced their status as artworks rather than mere reproductions. The market has shown time and again that collectors respond to scarcity, and that controlled production protects both the artist’s reputation and the collector’s investment. In the realm of photographic art, this protection is crucial: it ensures that the work is not lost in the flood of images, but preserved as part of a curated body of art.

Commodification can also be seen as a way of protecting photography from the flood of images in the digital age. With billions of photographs uploaded daily, most vanish into the ether, consumed briefly and then forgotten. Scarcity—whether expressed through unique processes, signed prints, or carefully managed editions—stands apart from this endless stream, offering something intentional, crafted, and enduring. It reminds us that photographic art is not just about circulation, but about permanence. A print that carries the weight of decision—the artist’s choice to make it part of a defined practice—signals that this image is not disposable content but art.

Finally, commodification allows photographic art to claim its place within the broader art market. Without scarcity, photography risks being undervalued, dismissed as endlessly reproducible and therefore lacking seriousness. With scarcity, photographic art asserts its intentionality, its crafted nature, and its rightful status alongside painting, sculpture, and other fine arts. For collectors, this matters. It reassures them that what they own is not just an image, but a work of art—rare, intentional, and enduring.

The Middle Ground – Limited Editions

If unlimited prints risk reducing photography to mass culture, and strict commodification risks turning it into a luxury investment, then limited editions offer a middle ground. They acknowledge photography’s reproducibility while still giving collectors something rare, intentional, and enduring. For photographic art, this balance is crucial. It allows the artist to embrace the democratic reach of the medium while also protecting the integrity of their vision.

A limited edition print is not simply a copy—it is part of a curated body of work. By signing and numbering each print, the photographic artist signals that this object belongs to a defined series, with a clear place in their practice. It is not just another image pulled from a file; it is a chosen artefact, carrying with it the artist’s intention. The act of limiting editions transforms the print from a mechanical reproduction into a crafted artwork, one that embodies the artist’s narrative and aesthetic choices.

For collectors, this matters deeply. Owning a limited edition is not about exclusion, but about participation. It creates a sense of belonging: the collector knows they hold something rare, yet still connected to a wider audience who share in the series. It is a way of engaging with the artist’s vision directly, rather than simply consuming an image in passing. In this sense, the limited edition becomes a bridge between artist and collector, a shared acknowledgement of the work’s significance.

Limited editions also protect the integrity of the work. They prevent dilution in the market, ensuring that each print retains its value and significance. In the world of photographic art, where images can otherwise be endlessly reproduced, this protection is vital. It reassures collectors that their investment is secure, but more importantly, it preserves the aura of the artwork—the sense that this print is part of a carefully considered body of art, not just another image circulating online.

At the same time, limited editions allow artists to balance accessibility with exclusivity. They make their work available, but in a way that respects both the democratic spirit of photography and the collector’s desire for rarity. An artist might choose to release open editions of certain works for wider audiences, while reserving limited editions for pieces that carry particular significance. This dual approach reflects the complexity of photographic art: it is both mass culture and fine art, both reproducible and intentional.

In this sense, limited editions are less about imposing scarcity and more about creating meaning. They remind us that photography is not just about circulation, but about intentionality. Each limited edition print is a statement of purpose, a way of saying: this image matters, and it has been chosen to exist in a defined, finite form. For those who value authenticity, owning a limited edition print is a way to step into the narrative, rather than simply observe it. It is a way of participating in the artist’s vision, of holding a piece of their practice in tangible form.

For collectors, engaging with such editions is not simply about ownership. It is about joining a narrative, becoming part of an archive that grows over time, and holding a piece of photographic art that has been deliberately shaped to last. Limited editions, in this sense, are not only a middle ground between accessibility and exclusivity—they are a way of affirming that photographic art deserves to be treated with the same seriousness, permanence, and respect as any other fine art.

Contemporary Relevance

The debate over commodification might sound like a relic of the 20th century, but it has never been more relevant than it is today. We live in an age of digital abundance. Billions of photographs are uploaded every day to social media platforms, most of them glanced at once and then forgotten. The sheer volume of images has created a paradox: photography has never been more present in our lives, yet individual photographs have never felt more disposable. The image has become a kind of currency—fleeting, interchangeable, and often stripped of context.

In this environment, scarcity takes on a new meaning. A limited edition print stands apart from the endless stream of digital images. It is not just another file in the cloud, but a crafted object with permanence. For collectors, this distinction matters. Owning a print that has been deliberately produced in small numbers is a way of resisting the ephemerality of the digital age. It signals that the image is not just content, but art. It is a declaration that this work has been chosen, shaped, and preserved with care.

There is also a cultural shift at play. As digital platforms homogenise style—think of the “Instagram aesthetic” with its predictable filters and compositions—limited editions offer a counterpoint. They remind us that photography can still be intentional, distinctive, and tied to an artist’s vision rather than an algorithm’s preferences. In this sense, scarcity is not just about market value; it is about authenticity. A limited edition print carries with it the aura of deliberation, the sense that it belongs to a narrative rather than a trend.

For photographers, limited editions provide a way to navigate the tension between accessibility and exclusivity. They allow images to circulate widely online, reaching audiences who may never see the physical work, while still offering collectors something tangible and rare. This dual presence—digital for reach, physical for permanence—reflects the reality of contemporary practice. It acknowledges that photography is both mass culture and fine art, and that the two can coexist without contradiction. The online image may be ephemeral, but the limited edition print endures.

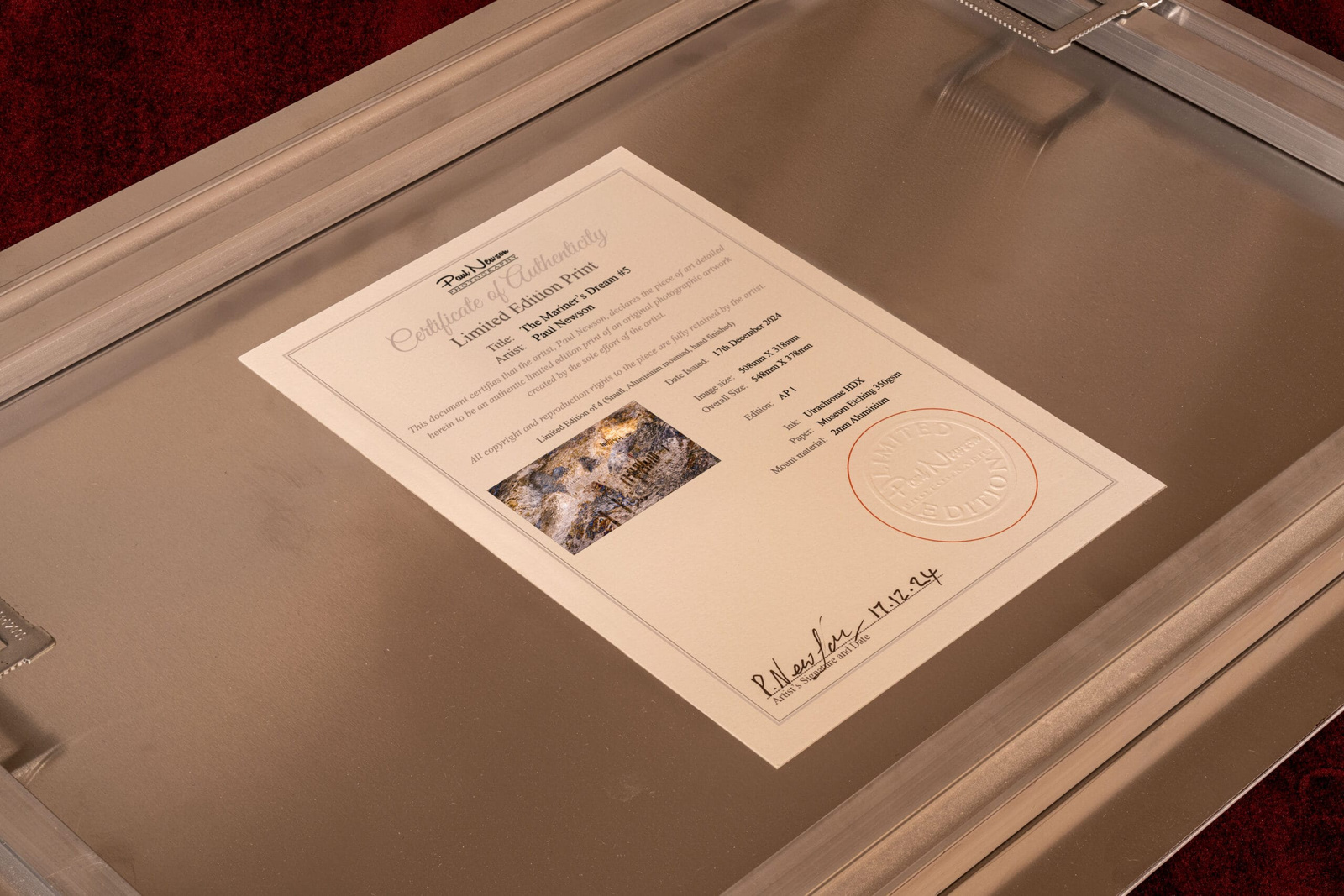

This is where the craft of the limited edition becomes central. A museum‑grade print, produced with archival inks on Hahnemühle Museum Etching paper, mounted to aluminium for strength and elegance, and signed with a certificate of authenticity, is not simply a photograph. It is a work of photographic art, engineered to last for generations. My own Limited Editions archive is built on this principle: each edition is created for collectors who value rarity, permanence, and provenance. Once an edition is sold out, it will never be reprinted. This permanence is not just a technical detail—it is part of the meaning of the work, a way of resisting the disposability of digital culture.

In short, the commodification of photographic prints is not an outdated debate. It is a pressing question in a world where images are everywhere, yet meaning is harder to find. Limited editions offer one answer: they create a space where photographs can be valued not just for their circulation, but for their intentionality and rarity. They remind us that photographic art is not content to be consumed and forgotten, but a crafted object designed to endure, to be lived with, and to be treasured.

Ethical and Market Considerations

Even if we accept that limited editions offer a middle ground, there are still ethical and market questions to consider. Is scarcity in photography genuine, or is it simply manufactured to create value? After all, a negative or digital file could produce countless identical prints. Limiting that output is a choice, not a necessity. Critics argue that this makes scarcity artificial, and therefore ethically questionable. They worry that scarcity imposed without artistic justification risks turning photographic art into a commodity stripped of meaning, valued only for its rarity rather than its vision.

This tension echoes broader debates in the art world. Painters and sculptors have long relied on uniqueness to establish value, but photography’s reproducibility complicates that model. When scarcity is imposed, is it a genuine reflection of artistic intention, or a concession to market forces? The answer often depends on context. A photographer who limits editions to preserve the integrity of a series may be seen as authentic, while one who does so purely to inflate prices risks accusations of cynicism. The ethical line is thin, and audiences are increasingly alert to whether scarcity feels earned or imposed.

There is also the issue of exclusion. By restricting supply, photographers inevitably raise prices. This can mean that only a small group of collectors can afford to participate, while wider audiences are left with digital reproductions or lower‑quality prints. Some see this as elitist, undermining photography’s democratic roots. Photography was once celebrated as the most accessible of art forms, a medium that could be shared widely across social classes. To restrict access through scarcity risks betraying that heritage. Yet others counter that exclusivity is part of what makes collecting meaningful—without it, prints risk being treated as disposable. For collectors, rarity is not simply about status; it is about knowing that the work they hold has been deliberately shaped to endure.

The role of galleries and institutions adds another layer. Galleries often insist on limited editions because they know scarcity drives value. Auction houses reinforce this by rewarding rarity with higher prices. In this sense, the market itself shapes the practice, sometimes leaving photographers little choice if they want their work to be taken seriously in the fine art world. For photographic artists, this can feel like a double bind: either embrace limited editions and be recognised as serious practitioners, or resist commodification and risk marginalisation. The market, in other words, has become a gatekeeper of legitimacy.

At the same time, new models are emerging. Online platforms allow photographers to sell directly to collectors, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. This opens up possibilities for more flexible approaches—such as offering both open editions for accessibility and limited editions for collectors. It suggests that commodification need not be rigid, but can be tailored to different audiences. A photographer might release open editions of certain works to maintain accessibility, while reserving museum‑grade limited editions for pieces that carry particular significance. This dual approach reflects the complexity of photographic art: it is both mass culture and fine art, both reproducible and intentional.

The ethical debate also intersects with technology. Blockchain and NFTs, for example, have introduced new ways of asserting scarcity in digital art. While controversial, these tools highlight the ongoing desire to create uniqueness in a reproducible medium. For some, they represent innovation; for others, they are another form of artificial scarcity. In either case, they show that the question of ethics in commodification is not static but evolving with technology.

Ultimately, the ethical and market considerations come down to intention. If scarcity is imposed cynically, it risks alienating audiences. But if limited editions are framed as part of an artist’s vision—an intentional way of shaping their body of work—then they can be seen as authentic rather than artificial. Scarcity, in this sense, is not about manipulation but about meaning. A museum‑grade limited edition, produced with archival materials, precision mounting, and hand‑signed certification, is not simply a restricted object. It is a crafted artwork, designed to endure, and its scarcity is part of its identity.

In this way, commodification becomes less about manipulation and more about meaning. It is not scarcity for its own sake, but scarcity as a marker of intentionality. For photographic art, this distinction is crucial. It allows artists to protect the integrity of their work, reassure collectors of its value, and ensure that prints are recognised not just as images, but as crafted objects designed to endure.

Conclusion – Invitation to Reflection

The commodification of photographic prints is not a simple story of good versus bad. On one side, there is the democratic ideal: photography as a medium that should remain open, reproducible, and accessible to all. On the other, there is the recognition that scarcity can elevate photography, protecting its integrity and giving collectors something tangible to hold onto. Both perspectives have merit, and both reflect the unique nature of photography as an art form caught between circulation and permanence.

What limited editions offer is a way of reconciling these tensions. They acknowledge photography’s reproducibility while still creating space for rarity and intentionality. They allow images to circulate widely in digital form, yet provide collectors with something crafted, signed, and enduring. In this sense, limited editions are not about exclusion, but about meaning. They remind us that photography is more than content—it is art, shaped by vision and care.

For those who value authenticity, owning a limited edition print is a way to participate in that vision. It is not just possession, but engagement: a chance to hold something rare, intentional, and lasting in a world where most images vanish into the digital stream. A limited edition print is not simply a photograph—it is a crafted object, produced with museum‑grade materials, precision mounting, and hand‑signed certification. It carries with it the aura of deliberation, the assurance that this work has been chosen to endure.

Whether one sees commodification as a necessary compromise or a philosophical challenge, limited editions stand as a thoughtful answer—balancing accessibility with exclusivity, democracy with rarity. They offer a way of protecting the integrity of photographic art in a world flooded with images, while still allowing audiences to engage with the work in meaningful ways. For collectors, they provide not only possession but participation: a chance to step into the narrative, to hold a piece of the artist’s vision, and to preserve it as part of a living archive.

In the end, the question of commodification is less about economics than about meaning. Limited editions remind us that photography, at its best, is not disposable content but intentional art. They invite us to reflect on what it means to own, to collect, and to engage with images in an age of abundance. And they offer a path forward—one that honours both the democratic spirit of photography and the enduring value of rarity, craft, and authenticity.

Perhaps the deeper lesson is that commodification is not a fixed state but a spectrum. At one end lies mass circulation, at the other exclusivity, and in between the nuanced practices that artists develop to balance reach with permanence. Limited editions are one such practice, but they are also a metaphor for photography itself: a medium that is both endlessly reproducible and profoundly intentional. To engage with a limited edition print is to acknowledge that paradox, to embrace photography’s dual identity as both democratic and rare.

One Comment

As someone who collects or appreciates photographic art, do you feel that the introduction of limited editions enhances the value and meaning of a print, or does it undermine photography’s original spirit of accessibility and openness?