Introduction: Setting the Scene

Photography has always been more than a technical exercise; it is a cultural act, a way of shaping memory, identity, and collective imagination. From its earliest days, the medium has been caught between science and art, between documentation and expression. The tools we use to make photographs are not neutral — they influence how we see, how we work, and how our images are received.

The debate between film and digital photography is therefore not simply about technology. It is about meaning. When we ask whether film is authentic art or outdated ritual, we are really asking broader questions: does the medium itself confer value? Does the process of creation matter as much as the final image? And how do cultural perceptions shift when technology changes the way we make and share photographs?

Film photography, with its tactile rolls, chemical baths, and delayed gratification, is often seen as a discipline that demands patience and intention. It carries with it a sense of ritual, a slowing down that many argue is essential to artistry. Digital photography, by contrast, is celebrated for its immediacy, its accessibility, and its ability to democratise creativity. It allows anyone to experiment freely, to learn quickly, and to share instantly.

Yet neither medium exists in isolation. Walk into a gallery today and you will find artists working in both traditions, sometimes even blending them. The question is not whether one is “better” than the other, but what each says about our relationship with art, authenticity, and time.

This long read will explore the debate from multiple angles: historical, philosophical, practical, and cultural. We will consider the arguments for film as a timeless craft, and the case for digital as a progressive tool. We will examine how audiences perceive each medium, how economics and ecology shape practice, and how hybrid approaches blur the boundaries.

The aim is not to deliver a verdict but to open a conversation. Photography thrives on diversity, and the richness of the medium lies in its contradictions. By the end, you may find yourself leaning towards one side, or you may see value in both. Either way, the debate itself is part of what keeps photography alive — a reminder that art is never static, but always evolving.

A Brief History of Film Photography

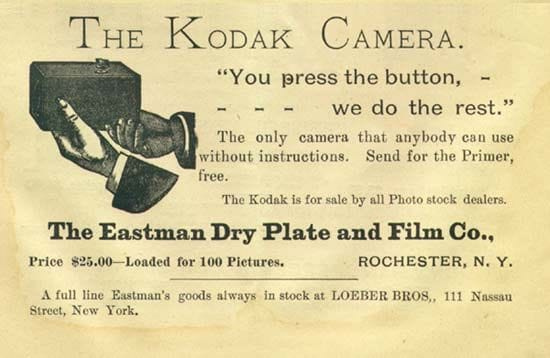

To understand why film continues to inspire debate, we need to look back at its origins. Photography itself was born in the early 19th century, with the daguerreotype announced in 1839 by Louis Daguerre in France. These early images were fragile, unique plates, treasured as marvels of science and art. The invention of roll film by George Eastman in the late 1880s transformed photography from a specialist pursuit into a popular pastime. Kodak’s slogan — “You press the button, we do the rest” — captured the spirit of democratisation. Suddenly, ordinary families could record their lives, and photography became woven into everyday culture.

Film matured quickly. By the early 20th century, it was the dominant medium for both professionals and amateurs. Black‑and‑white film defined the look of documentary photography, from war reportage to social reform projects. Colour film, introduced commercially in the 1930s, expanded the expressive palette, though it remained expensive and technically demanding for decades. Each advance in film technology — faster emulsions, finer grain, more reliable colour reproduction — shaped the way photographers worked and the kinds of stories they could tell.

The mid‑20th century was a golden age of film photography. Magnum photographers such as Henri Cartier‑Bresson, Robert Capa, and Eve Arnold used film to capture decisive moments and human drama. Their images became iconic not only because of their subjects but because of the distinctive qualities of film: the tonal range, the grain, the imperfections that lent character. In the art world, figures like Man Ray experimented with photograms and surrealist manipulations, while later artists such as Cindy Sherman used film to construct complex narratives of identity and performance. Film was not merely a tool; it was the medium through which photography established itself as a legitimate art form.

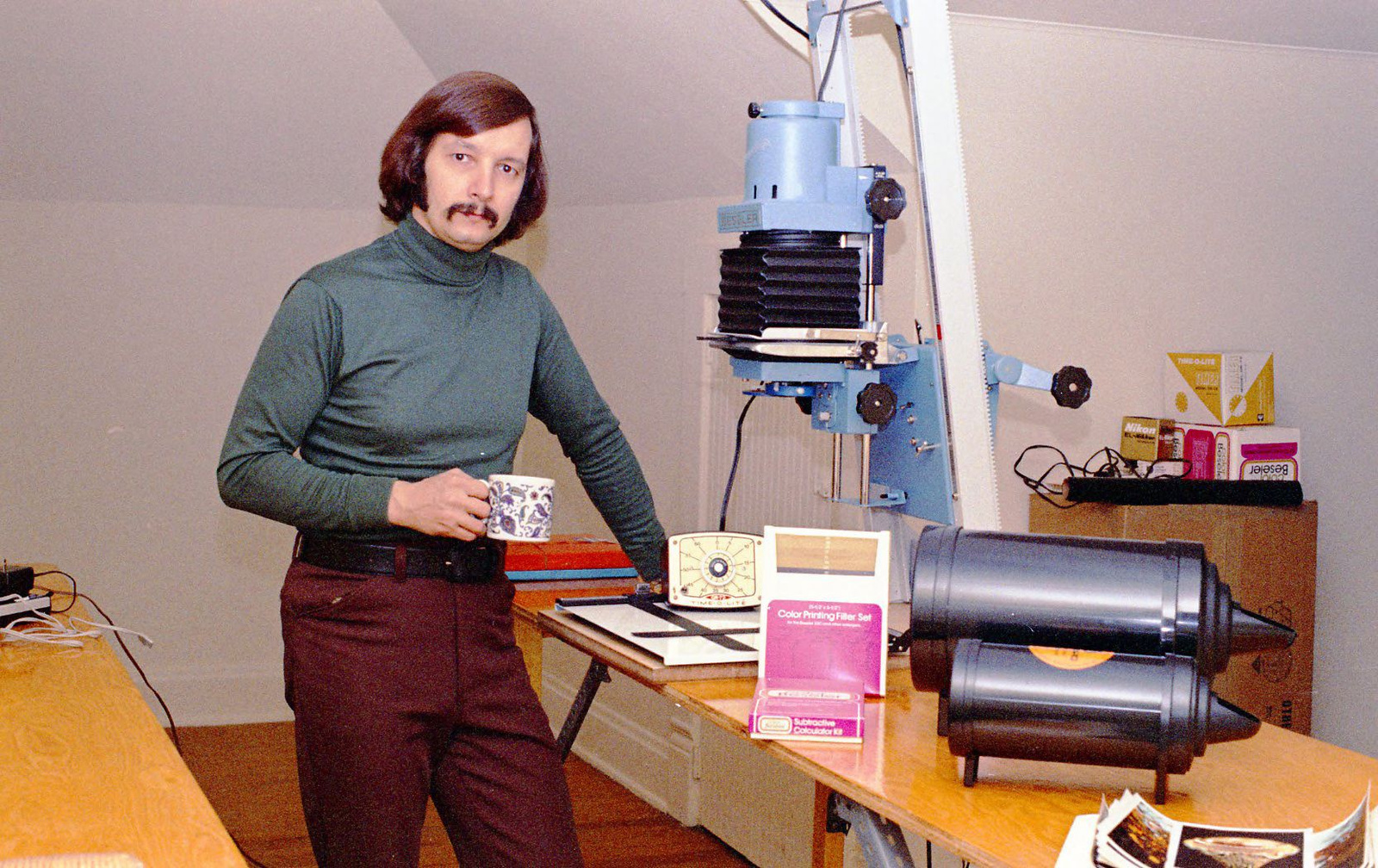

The ritual of film also became part of its identity. Loading a roll, advancing frames, and developing negatives in a darkroom were not incidental tasks but integral to the craft. Mistakes were costly, and patience was essential. The delayed feedback — waiting to see whether an image had succeeded — created a sense of anticipation that shaped the photographer’s mindset. For many, this discipline was what made photography meaningful. The process demanded respect, and the results carried weight.

Yet film was never without its critics. Even in its heyday, some argued that the chemical processes were cumbersome, the costs prohibitive, and the limitations frustrating. Photographers often had to balance artistic ambition with practical constraints: the number of exposures on a roll, the availability of light, the unpredictability of development. These challenges were part of the romance for some, but for others they were barriers to creativity.

By the late 20th century, film had become both ubiquitous and contested. It was the medium through which most of the world’s visual history was recorded — family albums, press archives, artistic portfolios — but it was also ripe for disruption. The arrival of digital photography in the 1990s did not simply replace film; it challenged the very assumptions about what photography could be. Film, once the unquestioned standard, became a choice, a statement, even a ritual. Its history is therefore not just technical but cultural: a story of how a medium shaped our collective memory and continues to influence debates about authenticity and art.

The Rise of Digital Photography

The late 20th century marked a turning point in the history of photography. For more than a century, film had been the unquestioned standard, shaping both professional practice and everyday snapshots. Yet by the 1990s, digital technology began to challenge this dominance. The first consumer digital cameras were clunky, expensive, and limited in resolution, but they hinted at a future where light could be captured not on chemical emulsion but as data.

By the early 2000s, digital photography had moved from novelty to mainstream. Improvements in sensor technology, storage capacity, and image quality made digital cameras increasingly attractive. For professionals, the ability to review images instantly was revolutionary. No longer did they need to wait for development to know whether a shot had succeeded. For amateurs, the freedom to shoot hundreds of frames without worrying about cost or scarcity opened up new possibilities for experimentation.

Digital photography also transformed the economics of the medium. While film required ongoing purchases of rolls and chemicals, digital involved a higher upfront cost but minimal expense thereafter. This shift made photography more accessible, particularly for those who wanted to learn quickly. Mistakes were no longer costly; they were simply deleted. The learning curve shortened dramatically, and photography became a more democratic art form.

The cultural impact of digital was equally profound. The rise of the internet and social media meant that images could be shared instantly across the globe. Photography became not only a way of recording personal memories but also a language of everyday communication. Platforms such as Flickr in the early 2000s, and later Instagram, turned digital photography into a social phenomenon. The abundance of images reshaped how we perceive value: photographs were no longer rare artefacts but ubiquitous expressions of identity.

For artists, digital opened new creative horizons. High‑resolution sensors allowed for unprecedented detail, while editing software such as Adobe Photoshop and Lightroom gave photographers control over every aspect of their images. Digital manipulation, once seen as controversial, became an accepted part of the creative process. Photographers could adjust exposure, colour balance, and composition with precision, creating images that were as much constructed as captured.

Yet this very convenience raised questions. Critics argued that digital risked diluting the discipline that film demanded. With film, each frame carried weight; with digital, the temptation was to shoot endlessly and “fix it later.” Some suggested that this led to a culture of over‑editing, where images were polished to perfection but stripped of their raw vitality. Others worried that the sheer abundance of digital images — billions produced daily — threatened to overwhelm the value of any single photograph.

Supporters countered that digital was not a dilution but an expansion of artistry. Just as darkroom techniques allowed film photographers to manipulate prints, digital tools provided a modern equivalent. The difference lay not in whether editing occurred but in how it was used — whether to enhance vision or to mask indecision. Moreover, digital’s accessibility meant that more voices could participate in the photographic conversation, enriching the medium with diversity and innovation.

By the 2010s, digital had become the dominant form of photography worldwide. Smartphones accelerated this trend, turning cameras into everyday companions. Photography was no longer a specialised practice but a universal language. Yet film did not disappear. Instead, it became a choice, a statement, even a counter‑cultural gesture. The rise of digital did not erase film; it redefined its role.

Digital photography, then, represents both progress and challenge. It has democratised creativity, expanded artistic possibilities, and reshaped cultural communication. But it has also raised questions about discipline, authenticity, and value. The debate is not whether digital is “better” than film, but how its convenience and abundance change the way we think about photography as art.

Authenticity and the Artist’s Hand

Few debates in photography stir as much passion as the question of authenticity. For many, film embodies a kind of truth that digital cannot replicate. The physicality of film — light striking emulsion, negatives stored in sleeves, prints emerging in trays of developer — creates a tangible connection between artist and image. Each photograph is a unique artefact, shaped by chemical reactions and the imperfections of analogue processes. Dust, scratches, and grain are not flaws but part of the character of the work.

Supporters of film often argue that this materiality anchors photography in the realm of art. Just as a painter’s brushstrokes reveal the hand of the artist, the marks of film reveal the process. The limitations of film — a finite number of exposures, the impossibility of instant review — demand a level of intention that digital does not. Every frame carries weight, and every mistake becomes part of the story. In this view, authenticity lies not only in the subject captured but in the discipline required to capture it.

The argument extends beyond aesthetics to philosophy. Walter Benjamin, in his famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction [paid link] (1935), spoke of the “aura” of an artwork — the unique presence that comes from its singular existence. Film photography, with its negatives and prints, arguably retains more of this aura than digital files, which can be copied endlessly without degradation. A silver‑gelatin print, for example, carries a sense of originality that a JPEG cannot.

Critics, however, challenge the idea that authenticity resides in film alone. They argue that digital photography is no less authentic, since the creative act lies in the photographer’s vision rather than the medium. Digital files may be intangible, but they are no less capable of expressing artistry. Moreover, digital allows for precision and control that film cannot match. The ability to adjust exposure, colour balance, and composition in post‑production can be seen as an extension of the artist’s hand, not a dilution of it.

There is also the question of honesty. Some claim that film is “truer” because it resists manipulation, but this is misleading. Darkroom techniques such as dodging, burning, and multiple exposures have long allowed film photographers to alter their images. Ansel Adams, for instance, famously used darkroom manipulation to achieve the dramatic tonal range in his landscapes. Digital editing is simply a continuation of this tradition, albeit with more powerful tools.

Audience perception complicates matters further. Many viewers instinctively associate film with authenticity, perhaps because of its historical role in documenting the 20th century. Iconic images of wars, civil rights movements, and cultural milestones were all captured on film, and this legacy shapes how we view the medium today. Digital, by contrast, is often associated with abundance and ephemerality — billions of images produced daily, many forgotten as quickly as they are shared. Yet this does not mean digital lacks authenticity; it simply embodies a different kind of truth, one rooted in immediacy and ubiquity.

Ultimately, the debate over authenticity is less about the medium than about our expectations of art. Do we value the trace of physical process, or the clarity of artistic intention? Film and digital embody different answers to that question, and both have their merits. Perhaps authenticity is not a property of the medium at all, but of the relationship between artist, image, and audience.

Convenience, Control, and the Digital Workflow

If film is often praised for its discipline, digital photography is celebrated for its convenience and control. The ability to shoot hundreds — even thousands — of frames without worrying about cost or scarcity has transformed the way photographers work. Mistakes can be corrected instantly, experiments can be pursued without hesitation, and learning curves are shortened dramatically. For many, this freedom is not a compromise but a liberation, allowing creativity to flourish without the anxiety of wasted resources.

Digital workflows also offer a level of precision that film cannot match. Exposure can be fine‑tuned, colours adjusted, and compositions refined with software tools that extend the photographer’s creative reach. Editing suites such as Adobe Lightroom, Capture One, and Photoshop have become as integral to the process as the camera itself, allowing artists to sculpt their images with meticulous care. The ability to work non‑destructively — to experiment without permanently altering the original file — encourages risk‑taking and innovation.

For professionals, this control translates into efficiency. Wedding photographers, for instance, can shoot thousands of images in a single day, confident that they will have ample material to deliver to clients. Commercial photographers can tether cameras directly to computers, reviewing results in real time and adjusting lighting or composition on the spot. In fields where deadlines are tight and expectations high, digital workflows are not just convenient; they are essential.

Critics argue, however, that this abundance of control risks undermining the spontaneity of photography. With film, the photographer must trust their instincts at the moment of capture; with digital, there is always the temptation to “fix it later.” Some suggest that this leads to a culture of over‑editing, where images are polished to perfection but stripped of their raw vitality. The ease of manipulation raises questions about honesty: when does editing enhance vision, and when does it cross into fabrication?

Yet others counter that digital editing is simply another form of artistry. Just as darkroom techniques allowed film photographers to dodge, burn, and manipulate prints, digital tools provide a modern equivalent. Ansel Adams famously described the negative as the score and the print as the performance. In the digital age, the RAW file is the score, and editing software is the performance. The artistry lies not in avoiding manipulation but in using it with intention.

Convenience also has cultural implications. Digital photography has made the medium more accessible than ever before. Smartphones put cameras in the hands of billions, turning photography into a universal language. This democratisation has broadened the range of voices and perspectives represented in visual culture. At the same time, it has created an overwhelming abundance of images, raising questions about value and attention. When photographs are everywhere, how do we decide which ones matter?

Ultimately, digital photography’s convenience and control have expanded the possibilities of the medium. The challenge for artists is to wield these tools with care, ensuring that freedom does not become excess, and that precision does not erase personality. Digital workflows can empower creativity, but they also demand responsibility. The ease of the medium is both its greatest strength and its greatest risk.

The Ritual of Film: Discipline or Nostalgia?

For many photographers, film is not simply a medium but a ritual. The act of loading a roll, advancing the frame, and waiting for the results carries a rhythm that shapes the creative process. Each step slows the photographer down, encouraging reflection and patience. This discipline is often cited as one of film’s greatest strengths: it forces the artist to be deliberate, to anticipate rather than react, and to accept the permanence of their choices.

Supporters of film argue that this ritual fosters a deeper connection to the craft. The limitations of film — a fixed number of exposures, the delay between capture and result — cultivate a sense of respect for each image. The process itself becomes part of the artistry, much like the rituals of painting or printmaking. The tactile handling of negatives, the smell of chemicals in the darkroom, and the anticipation of seeing prints emerge from trays of developer all contribute to a sensory experience that digital cannot replicate. For many, this ritual is inseparable from the artistry of photography.

The discipline of film also shapes the photographer’s mindset. Knowing that each roll contains only a finite number of frames encourages careful composition and thoughtful timing. The “decisive moment,” celebrated by Henri Cartier‑Bresson, gains weight when the photographer cannot simply fire off dozens of exposures. The ritual of film demands trust in instinct and skill, creating a sense of intimacy between artist and subject.

Yet critics see this differently. They suggest that the ritual of film is less about discipline and more about nostalgia. In a world where digital tools can achieve similar results with greater efficiency, clinging to film may be viewed as a romantic attachment to the past. The slower pace, the chemical processes, and the tactile handling of negatives are seen not as essential to art but as sentimental gestures. For some, the ritual is a way of reliving history rather than advancing creativity.

There is also the question of accessibility. Film requires specialised equipment, knowledge of darkroom techniques, and often significant expense. Digital, by contrast, allows anyone to participate without barriers. From this perspective, the ritual of film risks becoming an exclusive practice, cherished by a few but disconnected from the broader photographic community. The nostalgia associated with film can sometimes obscure its limitations, presenting it as a purer form of art when in reality it is simply one of many possible approaches.

At the same time, nostalgia itself can be a powerful force in art. Rituals, whether ancient or modern, shape how we experience creativity. The deliberate pace of film may feel outdated to some, but for others it is a source of inspiration. The act of slowing down, of embracing imperfection, can be a counterbalance to the speed and abundance of digital culture. In this sense, nostalgia is not necessarily regressive; it can be a way of reconnecting with values that risk being lost in the rush of technological progress.

The truth may lie somewhere in between. Film’s ritual is both discipline and nostalgia, both constraint and inspiration. What matters is not whether the ritual is outdated, but whether it continues to inspire meaningful work. For some artists, the ritual is essential to their practice; for others, it is unnecessary. The diversity of approaches reflects the richness of photography itself, a medium that thrives on contradiction and debate.

Audience Perception and Cultural Value

The way audiences respond to photographs often depends less on the image itself than on the medium through which it was created. Film photographs carry with them a certain aura: the knowledge that light was captured on a physical strip of emulsion, that the image exists as a tangible negative, and that it required deliberate craft to produce. For many viewers, this imbues film work with a sense of authenticity and permanence. Exhibitions of analogue prints often highlight this materiality, presenting the photograph as an object rather than just an image. The silver‑gelatin print, for example, is not only a picture but a physical artefact, with its own texture, weight, and fragility.

This aura is reinforced by history. The great documentary images of the 20th century — wars, civil rights marches, cultural revolutions — were all captured on film. Audiences instinctively associate film with truth, because it was the medium through which history was recorded. When we see a grainy black‑and‑white image of a protest or a portrait of a world leader, we do not question its authenticity; we accept it as part of the visual record. Film’s cultural value is therefore not only aesthetic but historical, rooted in its role as the witness of an era.

Digital photography, by contrast, is often associated with immediacy and ubiquity. The sheer abundance of digital images — from professional portfolios to social media feeds — can make them feel less rare, less precious. Yet this accessibility also broadens photography’s cultural reach. Digital images can be shared globally within seconds, allowing artists to connect with audiences far beyond the gallery walls. In this sense, digital photography has democratised not only the act of creation but also the act of viewing. A photograph no longer needs to be printed, framed, and exhibited to have impact; it can circulate online, reaching millions in moments.

Critics of digital argue that this abundance risks devaluing the medium. When billions of images are produced daily, how can any single photograph retain its impact? The saturation of visual culture means that audiences may scroll past extraordinary images without pause, their attention fragmented by the endless stream. Supporters counter that cultural value is not diminished by quantity but shaped by context. A digital image may be fleeting on a phone screen, but it can also be monumental when displayed in a curated exhibition or projected at scale. The same file can exist as both ephemeral communication and enduring artwork, depending on how it is presented.

Audience perception is also shaped by generational experience. Older viewers, who grew up with film, may instinctively value its materiality and discipline. Younger audiences, raised in the digital age, may see authenticity differently, locating it not in physical process but in immediacy and accessibility. For them, the ability to share an image instantly with friends or followers is part of its cultural meaning. Authenticity lies in connection rather than permanence.

The perception of value, then, is fluid. Film may be seen as rare and precious, digital as abundant and accessible — but both can command cultural weight when presented with intention. The audience’s response depends not only on the medium but on the framing, the narrative, and the space in which the image is encountered. A film print in a gallery may feel timeless; a digital image on a screen may feel transient. Yet both can move us, challenge us, and shape our understanding of the world.

Economic and Environmental Factors

Beyond questions of authenticity and ritual, there are practical considerations that shape the film versus digital debate. Cost is often the most immediate. Film requires rolls, chemicals, and specialised equipment, all of which add up quickly. A single project can involve significant expenditure, particularly if large prints or multiple rolls are needed. For students or emerging artists, the expense of film can be prohibitive, limiting experimentation and discouraging risk‑taking. Digital, by contrast, has a higher initial cost — cameras, lenses, and editing software — but once purchased, the marginal cost of each image is effectively zero. For many, this makes digital the more sustainable choice financially, especially in contexts where volume and speed are essential.

The economics of film also extend to time. Developing negatives, making contact sheets, and printing photographs are labour‑intensive processes. While this labour can be seen as part of the artistry, it also represents a significant investment. Digital workflows, by contrast, allow for rapid turnaround. A photographer can shoot, edit, and deliver images within hours, a pace that aligns with the demands of contemporary culture. In commercial fields such as advertising, journalism, and fashion, this efficiency is not optional; it is a necessity.

Environmental impact is another factor. Film photography relies on chemical processes that can be harmful if not disposed of properly. Developers, fixers, and other solutions contain substances that must be handled with care. While professional labs often follow strict protocols, the environmental footprint of analogue photography remains a concern. The production of film itself — involving plastics, metals, and chemical coatings — adds to this impact. Digital avoids these chemicals, but it is not without its own issues: electronic waste, battery production, and the energy demands of data storage all contribute to its ecological cost.

Supporters of film argue that its environmental impact is manageable, particularly when compared to the vast infrastructure required to sustain digital technology. They point out that film cameras, once purchased, can last for decades, whereas digital devices often become obsolete within a few years. Critics counter that digital’s efficiency and scalability make it the more responsible choice in a world increasingly conscious of sustainability. The ability to store thousands of images without physical materials reduces waste, even if the hidden costs of data centres and electronic recycling remain significant.

There is also a cultural dimension to these practical concerns. The expense and environmental footprint of film can be seen as part of its identity, reinforcing its aura of rarity and value. A film print is not just an image but an investment, both financial and ecological. Digital, by contrast, embodies abundance and accessibility, qualities that align with contemporary values of inclusivity and immediacy. The choice between film and digital is therefore not only practical but symbolic, reflecting broader attitudes towards consumption, sustainability, and cultural worth.

Economics and ecology, then, do not provide a simple answer. Both mediums carry costs, both financial and environmental, and the balance depends on context. For some artists, the expense and footprint of film are justified by its aesthetic and cultural value. For others, digital offers a more practical and sustainable path. The debate is not about eliminating one medium in favour of the other, but about recognising the trade‑offs and making choices that align with artistic vision and ethical responsibility.

Hybrid Practices and the Middle Ground

While the debate between film and digital often feels polarised, many contemporary photographers occupy a middle ground. Hybrid practices — combining analogue capture with digital editing, or using digital tools to emulate film aesthetics — have become increasingly common. This blending reflects a pragmatic approach: rather than choosing one medium over the other, artists select whichever tools best serve their vision.

For example, some photographers shoot on film to capture its distinctive tonal qualities, then scan negatives into digital formats for editing and distribution. This workflow preserves the aura of film while harnessing the flexibility of digital. Others work primarily in digital but apply filters or techniques that mimic the grain, colour shifts, or imperfections of film. In both cases, the boundaries between analogue and digital blur, creating a continuum rather than a binary.

Hybrid practices also reflect the realities of contemporary culture. Galleries and publishers often require digital files for reproduction, even when the original work was shot on film. Conversely, some digital photographers print their work on traditional papers to evoke the tactile presence of analogue. The interplay between mediums becomes part of the artistic statement, highlighting the tension between permanence and ephemerality, tradition and innovation.

Supporters of hybrid practices argue that this flexibility represents the true spirit of art. Photography has always evolved through technological change, and resisting innovation risks stagnation. By embracing both mediums, artists can honour tradition while exploring new possibilities. Hybrid workflows allow for experimentation without abandoning the values of discipline or authenticity.

Critics, however, suggest that hybrid approaches dilute the integrity of each medium. If film is valued for its authenticity, does digitising it undermine that quality? If digital is prized for its precision, does mimicking film reduce it to mere pastiche? These questions highlight the tension between purity and pragmatism in artistic practice. Some purists insist that film should remain analogue from start to finish, while others argue that digital should embrace its own identity rather than borrowing the aesthetics of the past.

Yet hybridity is not new. Even in the film era, photographers experimented with mixed techniques: combining negatives, hand‑tinting prints, or layering exposures. The digital age has simply expanded the range of possibilities. What matters is not whether a practice is “pure” but whether it produces meaningful work. Hybrid approaches demonstrate that photography is not bound by rigid categories but thrives on fluidity.

Ultimately, hybrid practices show that the debate is not about choosing sides but about expanding horizons. By acknowledging the strengths and weaknesses of both film and digital, artists can craft a language that is richer, more versatile, and more responsive to the complexities of contemporary culture. The middle ground is not a compromise but a fertile space where tradition and innovation meet.

Conclusion: Where Do We Go From Here?

The debate between film and digital photography is unlikely ever to be settled, because it is not simply about technology but about values. Film embodies ritual, discipline, and material authenticity; digital represents convenience, control, and democratic access. Each medium carries its own strengths and weaknesses, and each shapes the way we think about art.

For some, film remains a vital practice, a way of slowing down and honouring the craft. The tactile rituals of loading a roll, advancing frames, and developing prints are not just technical steps but part of the creative identity. Film’s imperfections — grain, scratches, tonal shifts — are celebrated as marks of authenticity, reminders that art is shaped by process as much as by vision. For others, digital is the natural evolution of photography, opening doors that film could never unlock. Its immediacy, precision, and accessibility align with the pace of contemporary culture, allowing more voices to participate and more stories to be told.

Many artists now move fluidly between the two, embracing hybrid approaches that reflect the complexity of contemporary practice. A photographer might shoot on film to capture its distinctive tonal qualities, then digitise negatives for editing and distribution. Another might work digitally but apply techniques that mimic the look of film. These hybrid practices demonstrate that the debate is not about choosing sides but about expanding horizons. Tradition and innovation are not enemies; they are collaborators.

What matters most is not whether we declare one medium superior, but how we use the tools available to us. Photography has always been about vision, not equipment. Whether captured on film or digital, an image gains meaning through the intention behind it and the context in which it is shared. A photograph is not defined by its medium but by its capacity to move us, to challenge us, to shape our understanding of the world.

Perhaps the real question is not “film versus digital” but “how do we make photographs that matter?” In that sense, both mediums remain alive, relevant, and capable of producing authentic art. The ritual of film may feel outdated to some, but for others it is a source of inspiration. Digital may seem ubiquitous, but it also offers unprecedented creative freedom. The choice is not binary; it is an invitation to explore.

As photography continues to evolve, the debate itself becomes part of its vitality. By questioning our tools, we deepen our understanding of our art. By challenging assumptions, we open new possibilities. Film and digital are not endpoints but stages in a journey — a journey that reflects not only the history of photography but the broader human desire to see, to remember, and to create.

One Comment

As someone who has worked with both film and digital, I often find myself torn between the tactile discipline of film and the creative freedom digital offers — do you think the process behind a photograph is as important as the final image itself, or does meaning lie solely in what the viewer sees?