Introduction

Photography has always carried an uneasy burden. From the moment the first images were fixed onto glass and paper, people began to treat them as more than pictures. They were seen as proof: evidence that something had happened, that someone had stood in a particular place, that history had unfolded in front of a lens. The phrase “the camera never lies” became a cultural shorthand, repeated so often that it almost felt like common sense.

And yet, from the very beginning, photographs have also been accused of deception. A carefully chosen angle, a cropped frame, a staged scene—each can transform what looks like fact into something closer to illusion. Even the most straightforward documentary image is shaped by decisions: where the photographer stood, what they chose to include, what they left out.

This tension between evidence and illusion is not a minor detail. It runs through the entire history of photography, from courtroom exhibits and press reportage to family albums and fine art. Photographs are trusted as witnesses, but they are also doubted as tricksters. They can testify, but they can also persuade.

A striking early example comes from the Crimean War. In 1855, Roger Fenton travelled to the front lines and produced more than 300 photographs under extremely difficult conditions. His images were widely praised as documentary evidence of the war, yet they were carefully composed to avoid scenes of death or suffering. One of his most famous works, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, shows a desolate road littered with cannonballs. Later analysis suggested that Fenton may have staged the scene by moving cannonballs into the road to heighten its drama. What looked like straightforward evidence of battle was, in fact, a crafted illusion—an image designed to persuade viewers back home of the war’s gravity without showing its horrors.

Around the same time, police forces began to adopt photography as a tool of identification. The mugshot, first used in the mid‑19th century, was intended as hard evidence of a person’s identity. Yet even here, illusion crept in. Lighting, angle, and expression could shape how a suspect appeared, sometimes reinforcing stereotypes or prejudices. What was presented as neutral documentation was, in practice, a constructed image.

These examples remind us that photography’s dual role—as evidence and as illusion—was present from the very start. In this long read we will explore both sides of the argument. We will look at the ways photographs have been used as evidence—sometimes with great authority, sometimes with disastrous consequences. We will also consider the ways in which photographs create illusions, whether deliberately or simply by the nature of the medium itself. Along the way, we will draw on history, philosophy, and practice, weighing the claims and counterclaims before leaving you to decide where the balance lies.

The Photograph as Evidence

From its earliest days, photography was celebrated as a mechanical witness. Unlike painting or drawing, which relied on the hand and imagination of the artist, the camera seemed to offer a direct transcription of reality. Light itself etched the image onto glass or paper, bypassing human fallibility. This apparent impartiality gave rise to the familiar phrase “the camera never lies,” a slogan that carried enormous cultural weight well into the twentieth century. The photograph was seen as a democratic truth-teller, a medium that could be trusted because it appeared to remove human bias from representation.

Early Uses in Documentation

By the mid‑nineteenth century, photographs were being adopted in policing and law. The mugshot, introduced in France by Alphonse Bertillon in the 1880s, became a cornerstone of criminal identification. Its purpose was straightforward: to provide indisputable evidence of a person’s appearance at a given time. Courts and police forces across Europe and America quickly embraced the practice, convinced that the photograph offered a neutral record of identity.

This was part of a wider movement to systematise human evidence. Bertillon’s anthropometric system measured ears, noses, and limbs, and photographs were used to anchor these measurements visually. The mugshot was not simply a picture; it was a tool of bureaucracy, a way of fixing identity in a world increasingly concerned with classification and control.

In science, too, photography was hailed as a breakthrough. Astronomers used it to capture celestial events that the human eye could barely glimpse. Doctors employed it to document medical conditions, creating visual archives of disease and treatment. Archaeologists relied on it to record excavations, preserving fragile artefacts and sites long after they had been disturbed. In each case, the photograph was treated as evidence—an objective record that could be studied, compared, and archived.

Journalism and Public Trust

The rise of photojournalism reinforced this belief. Newspapers and illustrated magazines began to publish photographs alongside written reports, lending visual authority to their stories. When readers saw images of wars, disasters, or political events, they often accepted them as proof that the events had occurred exactly as shown.

A famous example is Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936), taken during the Great Depression in the United States. The image of Florence Owens Thompson, surrounded by her children, became a symbol of hardship and resilience. For many, it was not simply a picture but evidence of the suffering endured by thousands of families. The photograph was widely credited with influencing public opinion and government policy.

Other documentary photographers of the era, such as Walker Evans and Gordon Parks, similarly used the camera to testify to social conditions. Their images were not just art but evidence—visual arguments for reform, proof of inequality, and records of lived experience.

Evidence in Art

Yet even in the realm of art, photographs can function as evidence. My Architecture series, for instance, records the built environment in monochrome detail. Each image is a document of a structure that exists in the world—evidence of human ambition, engineering, and history. A viewer can look at these works and recognise the lines of a modern tower or the textures of a heritage building. They testify to the presence of architecture in a particular place and time.

But the series also complicates this evidential role. By emphasising form, light, and perspective, the images transform buildings into something more than records. They become moments of contemplation, poetic illusions of permanence and grandeur. What begins as evidence of a structure becomes an aesthetic interpretation, reminding us that even the most factual photograph carries the shadow of artistry.

This tension is not unique. Consider Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies in the 1870s. On one level, they were scientific evidence, proving that a galloping horse lifts all four hooves off the ground. On another, they were aesthetic compositions, sequences of images that fascinated artists and scientists alike. Evidence and artistry were inseparable.

Arguments for Reliability

Supporters of photography’s evidential power point to several strengths:

- Detail beyond memory: A photograph can capture minute features that human recollection might miss or distort.

- Fixity in time: It freezes a moment, allowing later generations to examine it as if it were still present.

- Cross‑checking: Multiple photographs of the same event can corroborate one another, strengthening their credibility.

- Legal authority: Courts have long admitted photographs as evidence, recognising their value in establishing facts.

These arguments highlight photography’s unique ability to anchor memory and testimony. Unlike oral accounts, which shift with time, photographs appear stable. They can be revisited, compared, and scrutinised.

A Persistent Belief

Despite the rise of digital editing and synthetic media, many people continue to treat photographs as trustworthy. When a news story breaks, audiences instinctively look for images to confirm it. When a memory fades, they turn to photographs to restore it. Even in an age of scepticism, the photograph retains its aura of reliability.

This persistence speaks to a deeper cultural need. We want photographs to be evidence because they reassure us that the world can be captured, fixed, and remembered. Even when we know they can deceive, we continue to lean on them as anchors of truth.

The Photograph as Illusion

If photography has been trusted as evidence, it has also been accused—often with good reason—of being an illusion. From the earliest days, critics pointed out that photographs are not neutral transcriptions of reality but shaped artefacts. Every image is the result of choices: where the photographer stood, what they included, what they excluded, and how they presented the final print. The apparent transparency of the medium conceals layers of decision-making, intention, and cultural framing.

Philosophical Critiques

Writers such as Susan Sontag argued that photographs seduce us into believing we are seeing truth, when in fact we are only seeing fragments shaped by someone else’s perspective (On Photography, 1977). For Sontag, the danger lay in the photograph’s authority: it looked objective, but it was always partial.

Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida (1980), described photographs as both evidence of “that‑has‑been” and as deeply subjective, coloured by memory and emotion. A photograph may testify that something existed, but it cannot fix its meaning. Barthes’ famous meditation on the “punctum”—the detail that pierces the viewer—reminds us that photographs are experienced differently by each observer.

Other theorists, such as John Tagg in The Burden of Representation (1988), emphasised the institutional power behind photography. Images are not neutral; they are produced and circulated within systems—policing, journalism, advertising—that shape how they are read. These critiques remind us that photographs are never transparent windows; they are interpretive surfaces, embedded in structures of meaning.

Techniques of Manipulation

Illusion can be created in many ways:

- Cropping: Removing parts of an image to change its meaning. A protest photograph cropped tightly might suggest violence, while a wider frame could reveal peaceful crowds.

- Staging: Arranging subjects or objects to produce a desired effect. Portrait photographers have long staged settings to flatter sitters, while propagandists stage rallies to project unity.

- Retouching: Altering negatives or prints to erase or enhance details. In the nineteenth century, retouchers smoothed blemishes or added clouds to skies, creating images more pleasing than reality.

- Digital editing: Modern tools allow seamless manipulation, from colour correction to complete fabrication. Photoshop and similar software make it possible to alter images in ways that are undetectable to casual viewers.

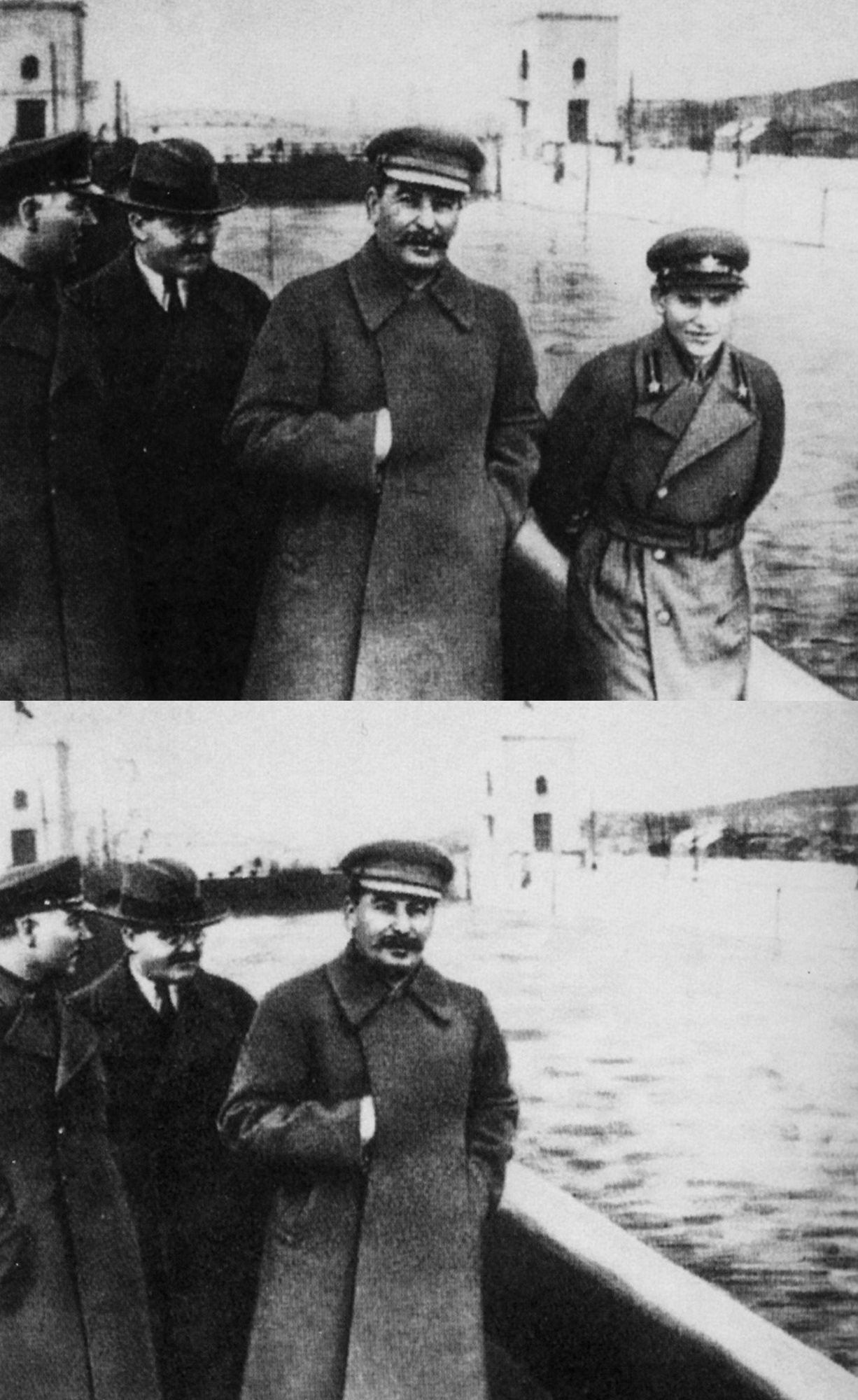

A notorious example comes from the Soviet Union, where official photographs were altered to remove purged figures from history. Leaders who fell out of favour were literally erased from group portraits, creating an illusion of unity and continuity. These doctored images were presented as evidence, but they were in fact political fictions.

Earlier examples exist too. In the American Civil War, photographers sometimes rearranged corpses on battlefields to create more dramatic compositions. These images were accepted as documentary evidence at the time, but later analysis revealed them as staged illusions.

Contemporary Illusions

In the digital era, manipulation has become easier and more convincing. Deepfakes—synthetic images and videos generated by artificial intelligence—can place people in situations they never experienced. While these are often discussed in terms of politics or celebrity culture, they highlight a broader truth: photography can no longer be assumed to represent reality.

Even everyday practices contribute to illusion. Social media filters smooth skin, brighten skies, and reshape bodies. Holiday snaps are cropped to remove clutter, selfies are staged to suggest spontaneity. These images may not be malicious, but they still present illusions—versions of reality designed to persuade. The illusion is not always grand deception; sometimes it is the subtle reshaping of everyday life to appear more polished, more enviable, more coherent than it really is.

The Case Against Trust

Critics argue that because photographs are so easily manipulated, they should never be treated as straightforward evidence. At best, they are persuasive tools; at worst, they are deliberate deceptions. The very qualities that make photographs powerful—their detail, their immediacy, their apparent realism—also make them dangerous, because they can be used to convince us of things that are not true.

This scepticism is not new. As early as the nineteenth century, commentators worried that photographs could be staged or altered. What has changed is the scale and speed of manipulation. In a world of instant sharing and viral circulation, illusions spread faster than corrections. The photograph’s authority is undermined not only by deliberate deceit but by the awareness that deceit is possible.

In this sense, the photograph as illusion is not simply a technical problem but a cultural condition. We live in an age where images are expected to persuade, where scepticism is necessary, and where trust must be earned rather than assumed.

The Role of Context

If photographs can be both evidence and illusion, then context is the stage on which their meaning is decided. A single image, stripped of explanation, can mislead or confuse. Add a caption, place it in a newspaper, hang it in a gallery, or present it in a courtroom, and its significance changes entirely.

Captions and Framing

A photograph of a crowd might be read as celebration or protest depending on the words beneath it. A portrait might be seen as heroic or criminal depending on whether it appears in a magazine profile or a police file. Context does not simply support the image; it actively shapes its interpretation.

Case Studies

- Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl” (1972): The photograph of Phan Thi Kim Phuc fleeing a napalm attack in Vietnam became a symbol of the war’s brutality. Yet its meaning was not inherent in the image alone. It was reinforced by the captions, the placement in newspapers, and the political climate of the time. Without the surrounding narrative, the image might have been seen as a local tragedy rather than a global indictment of war.

- Roger Fenton’s Crimean War photographs (1855): As noted earlier, his carefully composed images avoided scenes of death. Presented in Victorian parlours and publications, they were read as dignified records of war rather than as evidence of suffering. The absence of corpses was not accidental; it was a choice shaped by the expectations of his audience. Context turned omission into reassurance, presenting war as orderly rather than chaotic.

- Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936): While often cited as documentary evidence of Depression‑era hardship, its power was amplified by the way it was published and circulated. The photograph was used by government agencies to justify aid programmes, transforming it from a personal portrait into a political symbol.

The Audience’s Role

Context also includes the viewer. Each person brings their own knowledge, biases, and expectations to an image. A photograph of a ruined building might be seen as evidence of conflict, or as an aesthetic study in texture and form. The same image can testify to history or invite contemplation, depending on who is looking and why.

Negotiating Truth

This interplay of evidence, illusion, and context suggests that photographs do not carry fixed meanings. They are negotiated between the image, the setting, and the audience. A photograph may testify, but it never testifies alone.

Photography in Law and Justice

If photographs can be both evidence and illusion, then context is the stage on which their meaning is decided. A single image, stripped of explanation, can mislead or confuse. Add a caption, place it in a newspaper, hang it in a gallery, or present it in a courtroom, and its significance changes entirely. Context is not a passive frame; it is an active force that shapes interpretation, guiding audiences toward particular readings while closing off others.

Captions and Framing

A photograph of a crowd might be read as celebration or protest depending on the words beneath it. A portrait might be seen as heroic or criminal depending on whether it appears in a magazine profile or a police file. Context does not simply support the image; it actively shapes its interpretation.

Captions, headlines, and accompanying text can radically alter meaning. A photograph of a politician shaking hands may be captioned as evidence of diplomacy or as proof of collusion, depending on the editorial stance. Similarly, cropping can change emphasis: a wide shot of a demonstration may suggest peaceful assembly, while a tight crop on a single scuffle may imply violence. The photograph itself has not changed, but its context has transformed its significance.

The Audience’s Role

Context also includes the viewer. Each person brings their own knowledge, biases, and expectations to an image. A photograph of a ruined building might be seen as evidence of conflict, or as an aesthetic study in texture and form. The same image can testify to history or invite contemplation, depending on who is looking and why.

Audience reception can shift dramatically across cultures and generations. A wartime propaganda image may be read as patriotic in its original context, but decades later it may be seen as manipulative. Family photographs may be cherished as evidence of memory within one household, yet appear mundane or anonymous to outsiders. The viewer’s role is not passive; it is interpretive, constantly reshaping meaning.

The Architecture Series as an Example

My Architecture series illustrates this perfectly. On one level, the images are evidence of structures that exist in the world—proof of human ambition and engineering. Yet when placed in a curated collection, presented in monochrome, and framed as art, they invite a different reading. They become contemplative illusions, encouraging viewers to see architecture not just as shelter but as poetry.

The same photograph of a building could appear in a planning document, a tourist brochure, or a gallery exhibition. Each context would generate a different meaning: bureaucratic evidence, persuasive marketing, or aesthetic meditation. The image itself remains constant, but its interpretation shifts with its setting.

Negotiating Truth

This interplay of evidence, illusion, and context suggests that photographs do not carry fixed meanings. They are negotiated between the image, the circumstances of its presentation, and the audience’s expectations. Truth in photography is not absolute but relational.

A photograph may testify, but it never testifies alone. It speaks in dialogue with captions, institutions, and viewers. To understand photography, we must therefore look not only at the image but at the stage on which it is performed. Context is the lens through which evidence and illusion are reconciled—or contested.

Photography in Art and Culture

If courts and newspapers demand photographs as evidence, artists often embrace them as illusion. In the gallery, the photograph is freed from the burden of truth. It becomes a medium for symbolism, metaphor, and imagination. The same qualities that make photography persuasive in law or journalism—its apparent realism, its ability to freeze a moment—become tools for artists to question reality, to play with perception, and to invite audiences into worlds that are not strictly factual.

Photography as Conceptual Art

From the 1960s onwards, artists began to use photography not simply to record but to question. Sophie Calle, for example, staged investigations into strangers’ lives, blurring fact and fiction. Her projects often presented photographs alongside text, creating narratives that felt documentary but were tinged with performance. The viewer was left uncertain: was this evidence of real encounters, or an illusion crafted to provoke reflection?

Richard Long took a different approach. His walks across landscapes were documented with photographs, maps, and text. The photograph was not the artwork itself but evidence of an ephemeral act—the trace of a journey that could not be fully captured. In this sense, Long’s work highlights photography’s dual role: it testifies to something that happened, yet it also reminds us of what cannot be seen—the experience of walking, the passage of time, the feel of the land.

Other conceptual artists, such as Bernd and Hilla Becher, created typologies of industrial structures, photographing water towers and blast furnaces with clinical precision. Their images functioned as evidence of architectural forms, yet the repetition and framing transformed them into patterns, almost abstract illusions of order.

Surrealism and Staged Illusion

Earlier movements had already explored photography’s capacity for illusion. Surrealist photographers such as Man Ray and Claude Cahun used double exposures, collage, and theatrical staging to create dreamlike images. These works were never intended as evidence; they were deliberate illusions, challenging viewers to see beyond the literal.

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/104E4A, PD-US, Link

Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), for instance, transformed a woman’s back into a musical instrument through painted f‑holes, collapsing the boundary between body and object. Claude Cahun’s self‑portraits blurred gender and identity, presenting images that were simultaneously documentary and fantastical. Both artists demonstrated that photography could be a stage for imagination, not just a record of reality.

The Surrealists understood that photographs could persuade viewers to see the world differently. By manipulating light, composition, and subject matter, they created illusions that were not deceptions but invitations to dream.

Cultural Shifts

Photography’s role in culture has always been fluid. In family albums, it is evidence of memory—a record of birthdays, holidays, and milestones. In advertising, it is persuasion—images designed to sell products, lifestyles, or aspirations. In art, it is illusion—photographs that deliberately resist factual interpretation, instead offering metaphor and symbolism.

This fluidity means that the same photograph can shift meaning depending on context. A portrait might be evidence in a passport, persuasion in a fashion magazine, and illusion in a gallery. The medium itself does not dictate meaning; culture does.

Negotiating Authenticity

This cultural flexibility raises questions about authenticity. Is a staged photograph less “true” than a candid one? Or does it simply reveal another kind of truth—the truth of imagination, symbolism, or emotion?

Artists often argue that illusion is not deception but expansion. A staged photograph may not document reality in a literal sense, but it can reveal psychological or cultural truths. Cindy Sherman’s staged self‑portraits, for example, are not evidence of her daily life but explorations of identity, gender, and representation. They are illusions that expose deeper realities.

In art, then, authenticity is not measured by factual accuracy but by resonance. A photograph may be authentic if it captures an idea, a feeling, or a cultural condition—even if the scene itself was constructed. Illusion becomes a way of expanding what photography can say, rather than a betrayal of its evidential roots.

Contemporary Challenges

The digital age has multiplied photography beyond anything imaginable in the nineteenth or twentieth centuries. Billions of images are created and shared every day, most of them casual, fleeting, and unexamined. This sheer volume has changed the way we think about photographs: they are no longer rare artefacts but everyday signals, often consumed in seconds before being replaced by the next. The photograph has shifted from being a treasured object to a disposable unit of communication, a fragment in the endless scroll of digital life.

Digital Saturation

The abundance of images has paradoxical effects. On one hand, it makes photography more accessible than ever, allowing almost anyone to document events as they unfold. A protest can be captured from dozens of angles, a natural disaster recorded by witnesses across continents, a family moment preserved instantly on a phone. This democratisation of photography has given voice to individuals who might once have been excluded from visual history.

On the other hand, it dilutes the authority of any single image. When dozens of photographs of the same protest, disaster, or celebration circulate online, each with different angles and captions, the question of which one represents “truth” becomes harder to answer. The sheer volume of imagery can overwhelm rather than clarify. Instead of one decisive photograph shaping public opinion—as Lange’s Migrant Mother once did—we now have competing streams of visual evidence, each vying for attention, each vulnerable to manipulation.

AI and Synthetic Media

Artificial intelligence has introduced a new layer of complexity. Deepfakes and AI‑generated composites can produce images that look entirely convincing yet depict events that never occurred. These technologies blur the line between evidence and illusion to the point where traditional methods of verification struggle to keep pace. What once seemed like a reliable witness can now be fabricated with a few lines of code.

The implications are profound. In politics, synthetic images can be weaponised to discredit opponents or fabricate scandals. In law, doctored evidence could undermine trials. In everyday life, manipulated photographs can distort reputations, relationships, and memories. The photograph’s authority as evidence is eroded not only by deliberate deception but by the growing awareness that deception is possible.

Social Media and Virality

Platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and X (formerly Twitter) amplify this problem. Images spread rapidly, often detached from their original context. A photograph may be reposted with altered captions, cropped to change its meaning, or used to support narratives far removed from its original intent. In such environments, illusion thrives, and evidence becomes precarious.

Virality rewards impact rather than accuracy. A striking image may be shared thousands of times before anyone asks whether it is genuine. By the time corrections appear, the illusion has already taken root. The photograph’s persuasive power is magnified by speed, but its evidential reliability is diminished.

Ethical Questions

The contemporary landscape raises urgent ethical questions:

- Should platforms be responsible for verifying images before they spread?

- How can journalists and courts adapt to a world where manipulation is seamless?

- What role should audiences play in questioning and cross‑checking what they see?

These questions are not abstract. They shape how societies respond to crises, how justice is pursued, and how trust is maintained. If photographs can no longer be assumed to represent reality, then new systems of verification—technical, legal, and cultural—must emerge.

The Balance Today

In this environment, photography’s dual role as evidence and illusion is sharper than ever. The photograph remains powerful, but its authority is constantly challenged. Trust now depends less on the image itself and more on the networks of accountability that surround it: the credibility of the source, the transparency of the context, and the vigilance of the audience.

The digital age has not destroyed photography’s evidential power, but it has made it contingent. A photograph can still testify, but only if we ask the right questions about where it came from, how it was made, and why it is being shown. In this sense, the photograph today is not a silent witness but a contested artefact—its meaning negotiated in real time across platforms, cultures, and communities.

Conclusion

Photography has always lived in the tension between evidence and illusion. From Fenton’s cannonballs in the Crimean War to deepfakes circulating online today, the medium has been trusted as proof and doubted as trickery. Courts, journalists, and scientists have leaned on its authority, while artists have revelled in its capacity to deceive and transform. The photograph has never been a simple witness; it has always been a contested artefact, carrying the weight of both fact and imagination.

What emerges is not a simple verdict but a negotiation. Photographs are never pure evidence, nor are they mere illusions. They are shaped by context—by captions, by audiences, by institutions, and by the intentions of those behind the lens. A crime‑scene image may testify to fact, but it also persuades through framing. A family snapshot may preserve memory, but it also edits reality, omitting the chaos beyond the frame. An artwork may embrace illusion, but it still records something that existed in front of the camera, however fleeting or staged.

This negotiation has consequences. In law, it can determine guilt or innocence. In journalism, it can shape public opinion. In art, it can provoke reflection or unsettle assumptions. In everyday life, it can preserve memory or distort it. The photograph’s duality is not a weakness but a defining feature, one that forces us to confront the limits of vision and the power of interpretation.

In the end, perhaps the question is not whether photographs are evidence or illusion, but how we choose to read them. Do we demand certainty, or do we accept ambiguity? Do we treat them as witnesses, or as storytellers? The answer may shift depending on whether we are in a courtroom, a gallery, or scrolling through a feed. Each context invites a different kind of trust, a different kind of scepticism, and a different kind of engagement.

What remains constant is photography’s power. It can persuade, provoke, and preserve. It can mislead, but it can also reveal. It can freeze a moment in time, yet also open a door to imagination. To see photographs as either evidence or illusion is to miss their complexity. They are both—and it is in that duality that their enduring fascination lies.

Photography endures because it refuses to be pinned down. It is at once forensic and poetic, documentary and dreamlike, mundane and transcendent. Its history is a record of human ambition to capture truth, and of human creativity in bending truth into art. In our digital present, where images flood every screen, the challenge is not to decide once and for all whether photographs are evidence or illusion, but to remain alert to their shifting roles.

The photograph is not a verdict but a conversation. It asks us to look, to question, to interpret. It reminds us that seeing is never simple, and that truth itself is often a matter of perspective. That is why photography continues to matter—not because it resolves the tension between evidence and illusion, but because it keeps that tension alive.

One Comment

As someone who often relies on photographs to remember or understand key moments, I find myself wondering: do you think it’s still possible for me to fully trust a photograph as evidence, or should I always approach every image with a degree of scepticism—especially now that digital manipulation and AI are so widespread?