A New Era of Storytelling

Imagine a world without instant images from the front lines, where news of distant conflicts arrived only through words or an artist’s sketch. This was the reality until a perfect storm of technology and demand converged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As illustrated magazines proliferated globally, the public’s hunger for visual reporting grew exponentially. Readers wanted not just to read about events, but to see them.

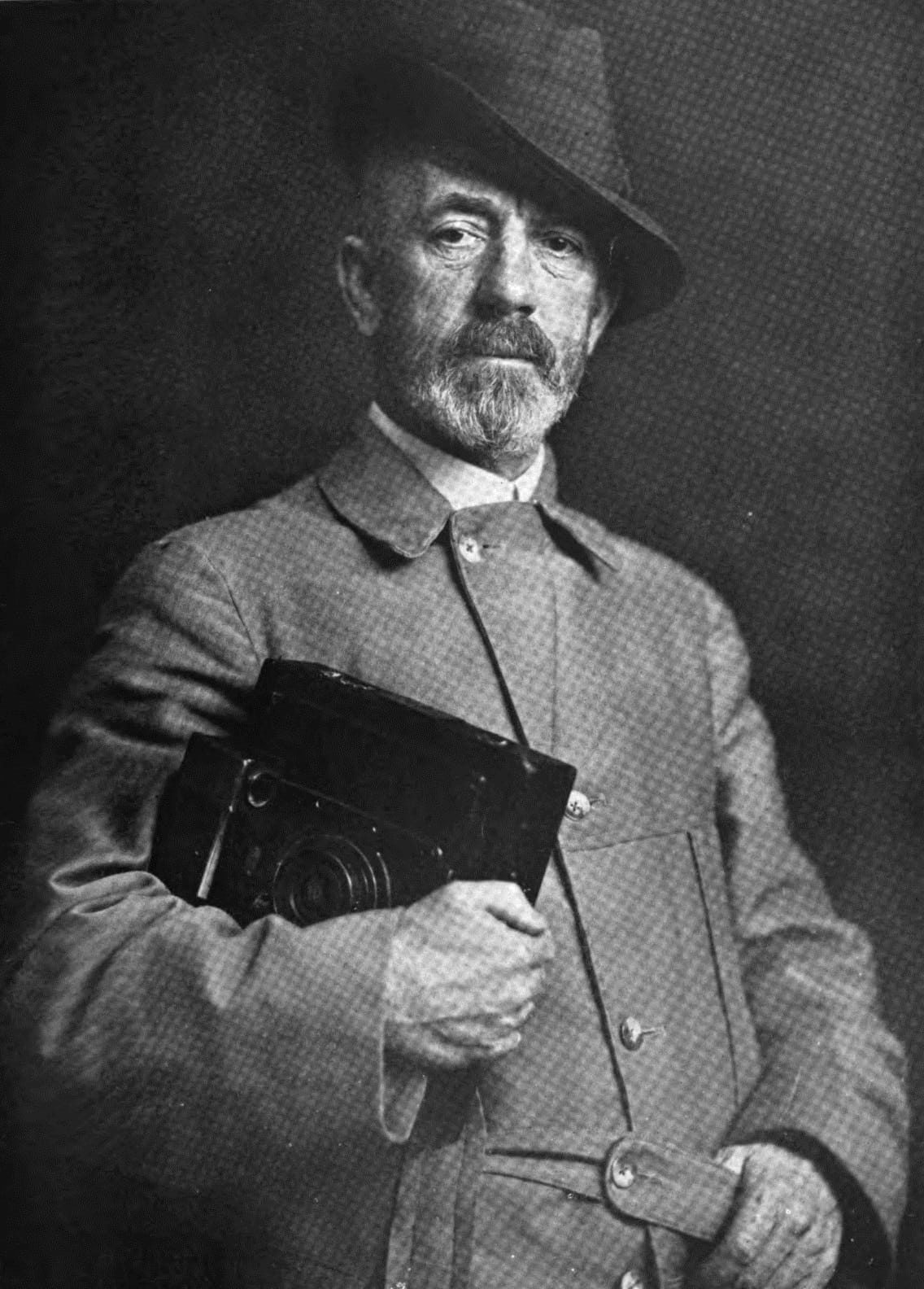

This demand coincided with the advent of lighter, more portable cameras and faster printing processes. No longer confined to the studio, photographers could now travel with soldiers, embedding themselves in the very heart of conflict. A new profession was born: the war correspondent with a camera. For the first time, photographers like Jimmy Hare, documenting the Spanish‑American War, and Horace W. Nicholls, covering the South African War, could bring the stark reality of conflict directly to the breakfast tables of millions. Their images were not just illustrations; they were evidence, testimony, and sometimes propaganda, shaping how entire nations understood war.

The impact was immediate. Readers who had once relied on second‑hand accounts were suddenly confronted with the faces of soldiers, the devastation of battlefields, and the human cost of empire. The photograph became a bridge between distant events and domestic life, collapsing the gap between “over there” and “right here.”

The Pioneers with a Lens

These early photojournalists were true adventurers, often risking their lives to capture fleeting moments of history. Their equipment, though lighter than the bulky cameras of earlier decades, was still cumbersome by modern standards. Tripods, glass plates, and boxes of chemicals had to be hauled across rough terrain, often under fire. Yet they persevered, driven by a conviction that the world needed to see what words alone could not convey.

Luigi Barzini, for instance, risked his life to capture the Russo‑Japanese War, producing images that revealed both the scale of modern conflict and the vulnerability of the individuals caught within it. In Mexico, Augustin Victor Casasola built an unparalleled visual archive of the Revolution, documenting not only battles but also the lives of ordinary people swept up in the upheaval. His photographs remain one of the most important records of that turbulent period, offering a perspective that written histories alone could never provide.

But with this new power came new anxieties. Governments quickly recognised the influence of photography in shaping public opinion. By the time of the First World War, strict censorship was imposed to control the photographic narrative. Images of dead soldiers, for example, were often suppressed, replaced with photographs that emphasised heroism, camaraderie, and sacrifice. The very fact that authorities felt compelled to censor photographs is a testament to their potency. A single image could sway morale, fuel dissent, or galvanise support.

The legacy of these pioneers was profound. Their work paved the way for the great picture magazines of the 20th century — Life, Vu, Picture Post — publications that would come to define visual journalism. The seeds planted by Hare, Nicholls, Barzini, and Casasola blossomed into a global culture of photo‑essays, where the photograph was no longer a supplement to the story but the story itself.

The Enduring Power of the Photographic Story

This journey from sketchy reportage to a cornerstone of modern media highlights a fundamental truth: a single, well‑composed photograph can tell a story more potent than a thousand words. A photograph does not merely illustrate; it condenses, symbolises, and provokes. It freezes a moment in time, yet it also opens that moment to endless interpretation.

It is this power of visual narrative that continues to inspire artists today. While the subjects may change — from battlefields to city streets, from revolutions to rituals — the principle remains the same. Great photography captures more than appearances; it captures atmosphere, emotion, and meaning. It invites us to see the world differently, to pause and reflect, to feel the weight of history or the intimacy of a fleeting gesture.

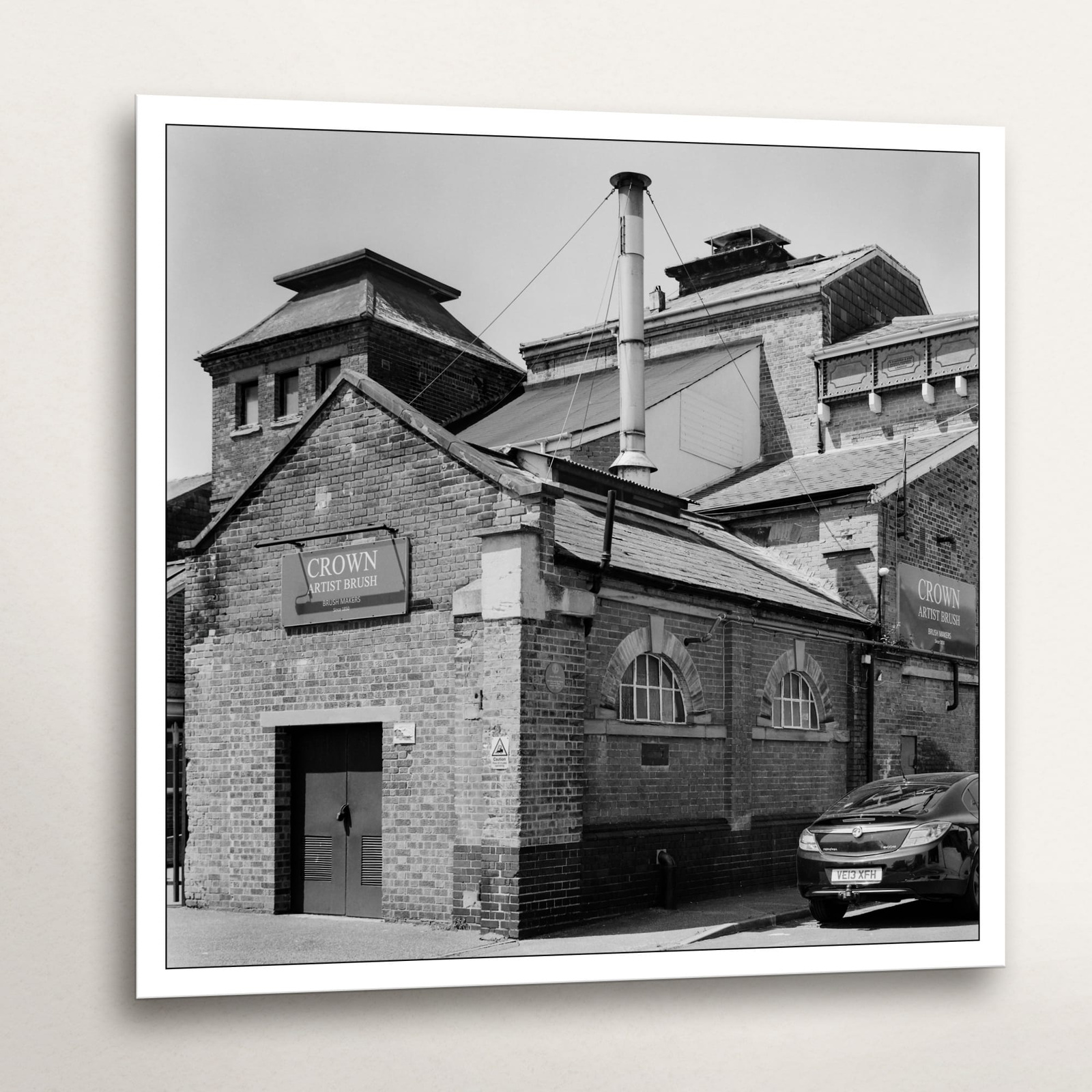

If you are captivated by the idea of owning a piece of visual storytelling that transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary, I invite you to explore a different kind of narrative in my own gallery. My Architecture collection, for instance, seeks to uncover the hidden drama and quiet poetry in the structures that surround us. Much like those early war photographers framed conflict, these works frame human ambition and history in a new light, turning familiar cityscapes into lasting works of art for your home.

Bringing History into Your Home

The birth of photojournalism taught us that a photograph is more than a record; it is a conversation between the photographer, the subject, and you, the viewer. To own a fine art print is to continue that conversation every day. Each piece becomes a story waiting to be lived with, a focal point for contemplation, and a statement of your appreciation for visual history.

I carefully craft each print to do justice to the original moment of capture, ensuring it becomes a treasured part of your space for years to come. Just as the pioneers of photojournalism brought the world’s conflicts into people’s homes, fine art photography today can bring history, symbolism, and imagination into yours — not as propaganda or reportage, but as enduring works of beauty and reflection.

One Comment

Which historic war photograph or photojournalist’s image has had the most profound impact on you, and why do you think photography can capture the realities of conflict in ways that written accounts sometimes cannot?