Soft Focus Before the Storm

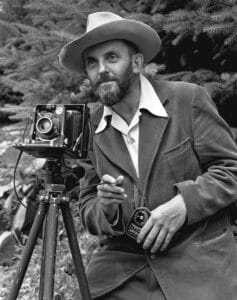

For many artists, a single, profound experience can redefine their entire creative compass, altering not only the way they see the world but also the way the world comes to see them. For the celebrated photographer Edward Steichen, that transformative force was the First World War.

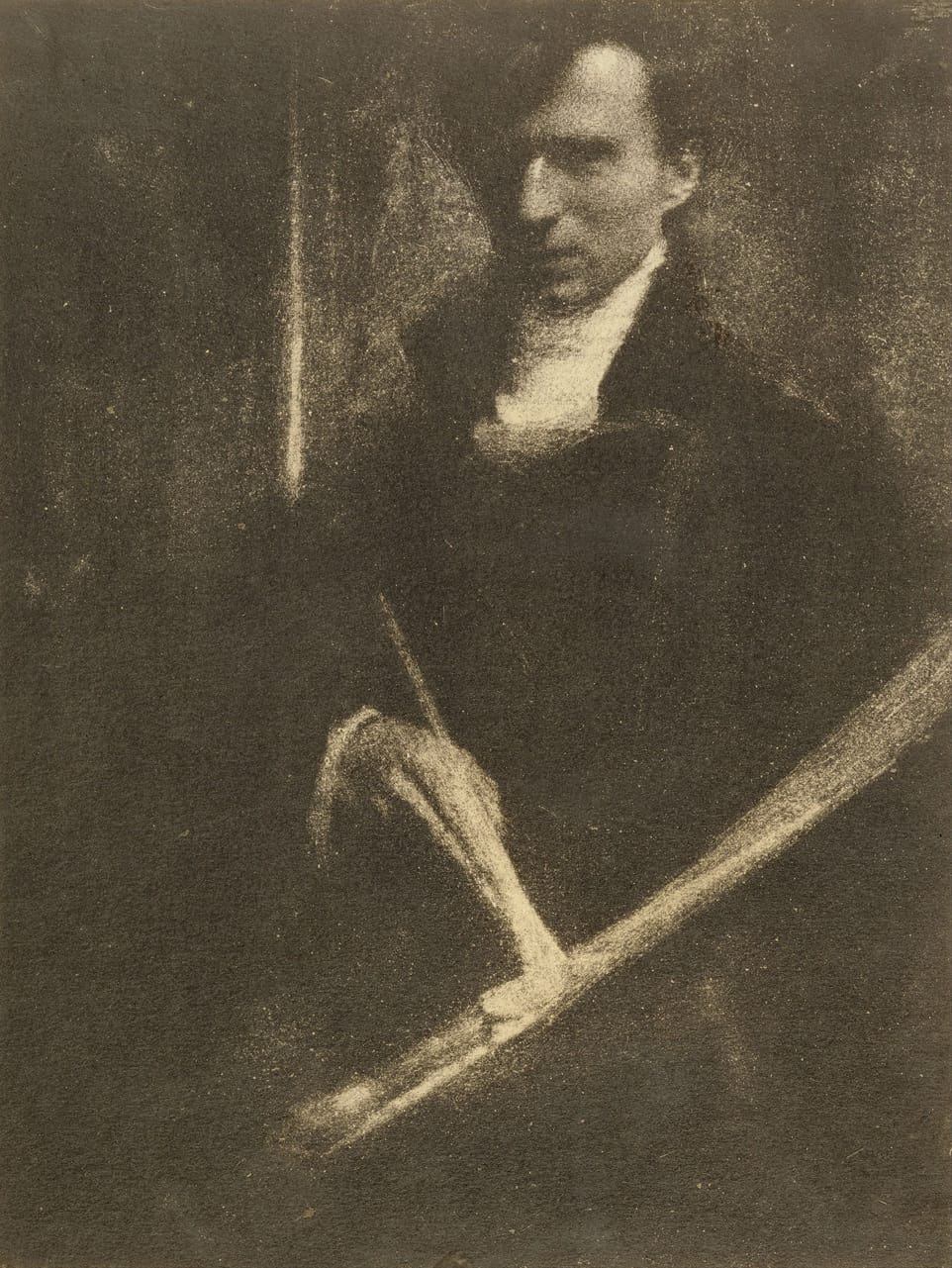

Before 1917, Steichen was already a towering figure in the Pictorialist movement, a style that sought to elevate photography to the level of fine art by imitating the painterly qualities of Impressionism and Symbolism. His images were renowned for their soft focus, romantic tones, and dream-like symbolism. They evoked mood and atmosphere rather than fact, often appearing more like delicate etchings than photographs. These works were undeniably beautiful, but they existed at a remove from the stark realities of the modern world, offering viewers a kind of visual escape rather than a confrontation with truth.

Into the Conflict: A New Role

When the United States entered the conflict in 1917, Steichen’s life and art took a dramatic and irreversible turn. He volunteered for service and was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Army Signal Corps. His artistic eye, once trained on ethereal landscapes and carefully staged portraits, was suddenly redirected toward a grimly practical mission. He was appointed head of aerial photography for the American Expeditionary Forces in France, a role that demanded not imagination but precision.

Aerial Photography and the Discipline of Clarity

High above the battlefields of Europe, the requirements of his work were brutally clear. There was no room for soft focus, poetic suggestion, or vague symbolism. The survival of soldiers and the success of entire campaigns depended on the absolute optical clarity and precise objectivity of every photograph. These images were not art in the traditional sense; they were maps, intelligence reports, and strategic tools. Each frame had to reveal the exact placement of enemy trenches, artillery, and fortifications. A blurred or misjudged exposure could mean the difference between victory and disaster.

This rigorous discipline fundamentally changed Steichen’s view of his medium. The war stripped away the decorative flourishes of Pictorialism and forced him to confront photography’s raw, documentary power. He later reflected that the experience had “knocked the ‘artiness’ out of me,” replacing it with a profound respect for the clarity and authority of a factual image.

After the Armistice: A Break with the Past

When the war ended and Steichen returned to civilian life, he found he could no longer work in his old style. The Pictorialist aesthetic that had once defined his reputation now felt hollow, even indulgent. He deliberately abandoned the ‘vaporous’ effects that had made him famous and embarked on a new artistic journey, one dedicated to exploring the raw, unadorned beauty of realism.

Experimentation and the White Cup

In the years that followed, he immersed himself in intense experimentation. He meticulously studied the effects of light, tone, and shadow on the simplest of subjects, stripping away narrative excess to focus on essence. It was during this period that he created his now-iconic series of a white cup and saucer. At first glance, the subject seemed almost banal, but under Steichen’s lens it became a profound meditation on form, luminosity, and the quiet drama of everyday objects. These photographs demonstrated that truth and beauty could coexist, that clarity could itself be poetic.

From Realism to Influence

This hard-won clarity and his masterful command of light became the hallmarks of his later work. They shaped not only his personal projects but also his commercial and institutional achievements. In the 1920s and 1930s, Steichen revolutionised fashion and portrait photography for Vogue and Vanity Fair, bringing a new sense of elegance and modernity to the genre. His images of celebrities, designers, and cultural icons were crisp, luminous, and direct, embodying the sophistication of a new age.

Later, as director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he applied the same principles to curatorial practice, most famously in the landmark exhibition The Family of Man (1955), which celebrated the universality of human experience through clear, powerful imagery.

Legacy and Contemporary Resonance

Steichen’s journey is a powerful reminder of how an artist’s style can evolve, not through gradual refinement alone but through seismic shifts brought on by history and circumstance. His story demonstrates that precision and truth can be as expressive as symbolism and mood, and that clarity itself can carry profound emotional weight.

You may find a similar dedication to form and light in my own photographic practice. My Architecture series, for instance, uses monochrome tones to explore the dramatic interplay of shadow and structure, revealing the quiet poetry of the built environment. Like Steichen’s post-war work, these images seek to uncover beauty not through embellishment but through precision, balance, and the eloquence of form. It is a collection for anyone who, like Steichen, finds lasting power in clarity, composition, and the truthful rendering of light.

One Comment

How do you think Steichen’s experience of war would have influenced your own approach to photography—would you embrace clarity and realism, or feel tempted to return to more symbolic and atmospheric styles like those in his early career?